203

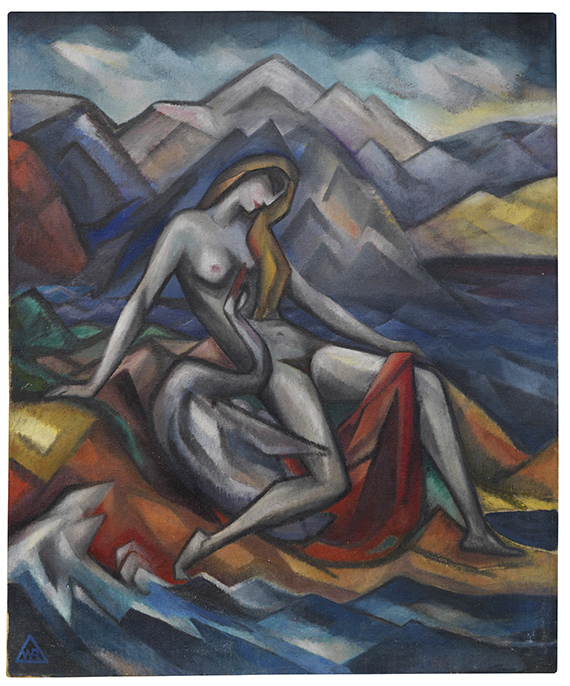

Wladimir Georgiewitsch von Bechtejeff

Leda und der Schwan, 1912.

Oil on canvas

Estimate:

€ 300,000 / $ 354,000 Sold:

€ 375,000 / $ 442,500 (incl. surcharge)

Leda und der Schwan. 1912.

Oil on canvas.

Bottom left monogrammed. 165 x 136 cm (64.9 x 53.5 in).

With two stamps of the paint supplies shop Richard Wurm, Munich, on the reverse. Stretcher hand-inscribed with the artist's name, the title and the inventory number of Galerie Arnold, Dresden. [AT/JS].

• Spectacular rediscovery.

• From the excellent collection of Werner Dücker, Düsseldorf.

• The whereabouts of large parts of Bechtejeff's oeuvre are largely unknown.

• Bechtejeff was part of the European avant-gard in the direct surroundings of the "Blauer Reiter".

• Most of the significant works from his early expressionist period are in acclaimed public collections.

• Capital work of impressive size.

We are grateful to Dr. Jelena Hahl-Fontaine for her kind expert advice.

PROVENANCE: Kunstverein Barmen (presumably acquired directly from the artist in December 1912, or on consignment, until March 1913).

Collection Werner Dücker, Düsseldorf (acquired from the above in March 1913).

Private collection Germany.

Saarbrücken art trade (acquired from the above around 25 years ago).

Private collection Saxony (acquired from the above).

EXHIBITION: Exhibition of 41 works from the Munich New Association of Artists at Kunstverein Barmen, December 1912 (without cat.).

Die neue Malerei. Expressionistische Ausstellung, January 1914, Galerie Ernst Arnold Dresden, cat. no. 14 (Title: "Leda", as loan from Werner Dücker, Düsseldorf, "unverkäuflich" (not for sale). With the gallery's hand-written inventory number on the stretcher).

LITERATURE: Account book of Kunstverein Barmen, "Geschäftsführung ab 1904" (management as of 1904), archive of the Von der Heydt-Museums Wuppertal (copy), fol. 92 ("Verkäufe an Private"/private sales).

Antje Birthälmer and Sabine Fehlemann, Die "Neue Künstlervereinigung München" und ihre Verbindungen zur rheinischen Kunstszene, in: Der Blaue Reiter und das Neue Bild 1909-1912. Von der "Neuen Künstlervereinigung München" zum "Blauen Reiter", book acccompanying the exhibition at Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, July 2 - October 3, 1999, pp. 276-285, here p. 284, ann. 65.

"Up until 1914 Bechtejeff's works were shown in all of Germany and were acquired by museums; in Otto Fischer's book about the Munich New Association of Artists from 1912, he is represented with a remarkable six illustrations. Alexej von Jawlensky saw him as a natural, Franz Marc regarded him as sensitive and his monumental painting [..] as innovative."

Jelena Hahl-Fontaine, in: Wladimir von Bechtejeff 1878-1971. Wiederentdeckt, Bonn 2018, p. 17.

Oil on canvas.

Bottom left monogrammed. 165 x 136 cm (64.9 x 53.5 in).

With two stamps of the paint supplies shop Richard Wurm, Munich, on the reverse. Stretcher hand-inscribed with the artist's name, the title and the inventory number of Galerie Arnold, Dresden. [AT/JS].

• Spectacular rediscovery.

• From the excellent collection of Werner Dücker, Düsseldorf.

• The whereabouts of large parts of Bechtejeff's oeuvre are largely unknown.

• Bechtejeff was part of the European avant-gard in the direct surroundings of the "Blauer Reiter".

• Most of the significant works from his early expressionist period are in acclaimed public collections.

• Capital work of impressive size.

We are grateful to Dr. Jelena Hahl-Fontaine for her kind expert advice.

PROVENANCE: Kunstverein Barmen (presumably acquired directly from the artist in December 1912, or on consignment, until March 1913).

Collection Werner Dücker, Düsseldorf (acquired from the above in March 1913).

Private collection Germany.

Saarbrücken art trade (acquired from the above around 25 years ago).

Private collection Saxony (acquired from the above).

EXHIBITION: Exhibition of 41 works from the Munich New Association of Artists at Kunstverein Barmen, December 1912 (without cat.).

Die neue Malerei. Expressionistische Ausstellung, January 1914, Galerie Ernst Arnold Dresden, cat. no. 14 (Title: "Leda", as loan from Werner Dücker, Düsseldorf, "unverkäuflich" (not for sale). With the gallery's hand-written inventory number on the stretcher).

LITERATURE: Account book of Kunstverein Barmen, "Geschäftsführung ab 1904" (management as of 1904), archive of the Von der Heydt-Museums Wuppertal (copy), fol. 92 ("Verkäufe an Private"/private sales).

Antje Birthälmer and Sabine Fehlemann, Die "Neue Künstlervereinigung München" und ihre Verbindungen zur rheinischen Kunstszene, in: Der Blaue Reiter und das Neue Bild 1909-1912. Von der "Neuen Künstlervereinigung München" zum "Blauen Reiter", book acccompanying the exhibition at Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, July 2 - October 3, 1999, pp. 276-285, here p. 284, ann. 65.

"Up until 1914 Bechtejeff's works were shown in all of Germany and were acquired by museums; in Otto Fischer's book about the Munich New Association of Artists from 1912, he is represented with a remarkable six illustrations. Alexej von Jawlensky saw him as a natural, Franz Marc regarded him as sensitive and his monumental painting [..] as innovative."

Jelena Hahl-Fontaine, in: Wladimir von Bechtejeff 1878-1971. Wiederentdeckt, Bonn 2018, p. 17.

From Jelena Hahl-Fontaine

"Leda and the Swan" – Rediscovery of a monumental mythological composition

With its timeless beauty, a subtle eroticism and a refined composition, this typical, large-format painting immediately captivates the observer. In order to celebrate the naked female body without facing legal consequences, a mythological theme was used in pretense – as was common not only with the Russian artist, but throughout art history: In this case "Leda and the Swan", a very popular motif. As offspring of wealthy landed gentry, Wladimir von Bechtejeff had private tutors, who absolutely needed to be well versed in mythological topics, from an early age on. Apparently he was particularly fond of it, which explains why he repeatedly chose themes from this childhood treasure chest later in his life, especially for his large-format "official" paintings. However, the art-historical significance of the picture is largely owed to its time of creation around 1912/13, when French Cubism became known in Germany through a grand exhibition which immediately inspired Bechtejeff, Franz Marc and August Macke. The difference in style of Bechtejeff‘s "Rossebändiger" (Lenbachhaus Munich, cat. Murnau, p. 93) and the "Leda", which was created shortly thereafter, is obvious: instead of a flowing and boisterous movement, we find a stylization of a harder, more Cubist manner, which we not only see in the mountains and rocks, but even the sea waves appear as edgy and jagged shapes. Alone Leda's beauty remains untouched; Deformations of the human body that might call reminiscence of Picasso are out of the question for Bechtejeff the sensitive aesthete. He treated the figure of Leda and the swan that caresses her as a typical "line ornament" committed to Art Nouveau and the cloisonné technique, only a little more rigidly than in his earlier paintings, for example in "Zwei badende Frauen" "from 1910 (Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, cat. Murnau, p. 80). The painting "Leda" undoubtedly represents an important milestone between the "Rossebändiger", 1912, and "Diana auf der Jagd", 1912/13 (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, cat. Murnau, p. 91). The "Self-Portrait as a Harlequin" from 1914-1916 (Collection Boris and Marina Molchanov, cat. Murnau, p. 101), on the other hand, is a document of the next step the artist made when he refined the Cubist method.

1902–1914 – On the key importance of the Munich years for Bechteev's work

The pictures that can be found in several German museums still bear witness to the importance of Bechteev during his time in Munich from 1902 to 1914; the painting "Rossebändiger", for example, has been in possession of the Lenbachhaus in Munich since the 1960s and is mentioned in many publications on the Expressionist era. The following positive judgment from his fellow artist Franz Marc from 1910 is just one of many appreciative statements: "To me the most important one of the artists of the 'Neue Münchener Künstlervereinigung' (Munich New Association of Artists) by far seems to be Wladimir von Bechteev. He achieved what Marées struggled with in vain, and what Feuerbach failed to achieve. Both sought to depict man with the exhausted means of Renaissance, without daring to integrate him into their ornamental compositions as line ornament. The poised use of the large line for form and grouping, the delicacy of Bechteev‘ colors, both surpass the attempts that Feuerbach and Trübner made on the same problem by far. "

Another fellow artist, Adolf Erbslöh, who took over chairmanship of the association from Kandinsky, did not hesitate to acquire works from Bechteev and soon furnished his house with a monumental mural, several paintings and a female bronze . Jawlensky saw his younger fellow countryman as a "natural", took him into care and recommended him to the art educator Knirr so he could complete the training he had begun in Moscow and continued in Venice and with Cormon in Paris. The renowned art historian Richard Reiche passed his judgment in 1912:

"It is our duty and pleasure to [.] testify to the outstanding intellectual and artistic contribution of the Russian artists in Munich to the formation and the success of the 'Neue Künstlervereinigung' at that time. [.] Bechteev and baroness Werefkin were strong elements of this union."

Important and frequent participations in exhibitions and sales of his paintings until 1914 also speak for Bechteev's position in the German art scene at that time.

First World War and return to Russia – Bechteev's retreat into graphic art

The development of progressive painting saw a sudden halt with the outbreak of World War I. Being a Russian citizen, Bechteev was immediately expelled from Germany and was forced to leave numerous pictures that occasionally appear on the art market behind. As a former cavalryman he was immediately drafted into the army, however, he was soon soon transferred to the state circus for disciplinary reasons. This gave him the fortunate opportunity to develop his style of Cubism in costume- and set designs. There is proof of his participation in the exhibition "Vom Impressionismus zur ungegenständlichen Malerei“ (From Impressionism to Abstract Painting) at the State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow in 1918/19. Unfortunately, the epoch of the Russian avant-garde‘s artistic awakening lasted only a few years. As a member of the nobility, Bechteev, along with his wife, was exiled to Siberia for eight years. While he wasn‘t able to paint in exile the ability to make drawings, now in a fine "naturalistic" manner as abstraction was simply forbidden, must have comforted him a little and his mastery as a graphic artist was met with official recognition. Back in Moscow he soon achieved great fame as illustrator of around 120 books. His drawings and watercolors were also shown in Russian museums on numerous occasions.

The art-historical appreciation of Bechteev's outstanding early work

What about today? Rediscovered, also in Russia, where the lack of early works is deeply regretted. The break marked by war I and the Iron Curtain could not be bridged, even if the number of more than 60 exhibition participations and 200 catalog entries and articles in Germany, but mostly in Russia (see Ildar Galeyev, 2005) dispel any doubt regarding Bechteev‘s importance. In 2018 a large solo exhibition was finally shown at the Murnau Castle Museum, accompanied by a beautiful catalog that impressively documents.

Jelena Hahl-Fontaine (formerly Hahl-Koch), Dr. phil. in art history and Slavic studies, former curator at the Lenbachhaus Munich, visited and interviewed Bechteev in Moscow in the 1960s. Since then she has researched and published on Bechteev, Kandinsky and the art of the "Blaue Reiter".

On the provenance – In Barmen and Dresden

Bechteev's "Leda" is not only fascinating in terms of its artistic appeal, it also has a fascinating background story. Soon after it was made in 1912, the large picture was sent to Barmen, where the local art association under Richart Reiche had become established as a vibrant center of modernity. In December 1912, Bechteev took part in an exhibition of 41 works by artists of the expressionistic "Neue Künstlervereinigung München" (New Munich Art Association, N.K.V.M.), the nucleus of the "Blaue Reiter". And as luck would have it, the Düsseldorf collector Werner Dücker (1887–1945, died as a prisoner of war) also exhibited his outstanding collection in Barmen. Eighteen paintings and one sculpture by French artists such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, but also by outstanding German painters like Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and, last but not least, Vladimir von Bechteev, were on display. Even though neither exhibition was accompanied by a catalog, it is little surprising that Dücker discovered "Leda" browsing the N.K.V.M. exhibition rooms. A little later he bought the picture directly from Kunstverein Barmen, as it is noted in its business records. In January 1914, the Dresden gallery Arnold finally presented the work in the important exhibition "Die neue Malerei" (The New Painting) organized by Richart Reiche, the first major Expressionism show in Dresden. It came as a loan from Werner Dücker, who had marked his "Leda" as ‘not for sale‘ in the catalog.

A fascinating collector

The collector Werner Dücker, a Catholic from the Rhineland, was, as far as the scanty sources indicate, a dazzling personality: wealthy and sophisticated, progressive and liberal. Dücker and his wife, the sculptress Marta Zahn, were close friends of Richard Schultz, through whom they got into contact with the lively gay scene in Berlin (cf. Karl-Heinz Steinle, der literarische Salon bei Richard Schultz, Berlin 2002). The group of friends met at literary salons, were avid nudists and followers of Adolf Koch, a luminary of nudism, and were regulars at the legendary "Westend-Klause" with the innkeeper Walter Franke's. Werner Dücker was clearly attracted by the sexual freedom and openness that modernity had to offer. And Bechteev's "Leda mit dem Schwan" is also a work with a clearly erotic appeal that is as elegant as it is succinct. It is not surprising that Werner Dücker was willing to spend the considerable sum of 1650 Reichsmark on the work in 1913.

But Dücker was not able to enjoy his "Leda" for very long. In 1923 he lost all of his fortune due to the hyperinflation. Marta then opened a fashion store to make more money than she could through sculpting, and the highly significant art collection had to be sold. Richard Schultz took over some of the works from his friend Dücker – but there is no reference to "Leda" in the Schultz estate. It was only a few decades ago that Bechteev's masterpiece – unidentified as such – reappeared in a private collection. [AT]

"Leda and the Swan" – Rediscovery of a monumental mythological composition

With its timeless beauty, a subtle eroticism and a refined composition, this typical, large-format painting immediately captivates the observer. In order to celebrate the naked female body without facing legal consequences, a mythological theme was used in pretense – as was common not only with the Russian artist, but throughout art history: In this case "Leda and the Swan", a very popular motif. As offspring of wealthy landed gentry, Wladimir von Bechtejeff had private tutors, who absolutely needed to be well versed in mythological topics, from an early age on. Apparently he was particularly fond of it, which explains why he repeatedly chose themes from this childhood treasure chest later in his life, especially for his large-format "official" paintings. However, the art-historical significance of the picture is largely owed to its time of creation around 1912/13, when French Cubism became known in Germany through a grand exhibition which immediately inspired Bechtejeff, Franz Marc and August Macke. The difference in style of Bechtejeff‘s "Rossebändiger" (Lenbachhaus Munich, cat. Murnau, p. 93) and the "Leda", which was created shortly thereafter, is obvious: instead of a flowing and boisterous movement, we find a stylization of a harder, more Cubist manner, which we not only see in the mountains and rocks, but even the sea waves appear as edgy and jagged shapes. Alone Leda's beauty remains untouched; Deformations of the human body that might call reminiscence of Picasso are out of the question for Bechtejeff the sensitive aesthete. He treated the figure of Leda and the swan that caresses her as a typical "line ornament" committed to Art Nouveau and the cloisonné technique, only a little more rigidly than in his earlier paintings, for example in "Zwei badende Frauen" "from 1910 (Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, cat. Murnau, p. 80). The painting "Leda" undoubtedly represents an important milestone between the "Rossebändiger", 1912, and "Diana auf der Jagd", 1912/13 (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, cat. Murnau, p. 91). The "Self-Portrait as a Harlequin" from 1914-1916 (Collection Boris and Marina Molchanov, cat. Murnau, p. 101), on the other hand, is a document of the next step the artist made when he refined the Cubist method.

1902–1914 – On the key importance of the Munich years for Bechteev's work

The pictures that can be found in several German museums still bear witness to the importance of Bechteev during his time in Munich from 1902 to 1914; the painting "Rossebändiger", for example, has been in possession of the Lenbachhaus in Munich since the 1960s and is mentioned in many publications on the Expressionist era. The following positive judgment from his fellow artist Franz Marc from 1910 is just one of many appreciative statements: "To me the most important one of the artists of the 'Neue Münchener Künstlervereinigung' (Munich New Association of Artists) by far seems to be Wladimir von Bechteev. He achieved what Marées struggled with in vain, and what Feuerbach failed to achieve. Both sought to depict man with the exhausted means of Renaissance, without daring to integrate him into their ornamental compositions as line ornament. The poised use of the large line for form and grouping, the delicacy of Bechteev‘ colors, both surpass the attempts that Feuerbach and Trübner made on the same problem by far. "

Another fellow artist, Adolf Erbslöh, who took over chairmanship of the association from Kandinsky, did not hesitate to acquire works from Bechteev and soon furnished his house with a monumental mural, several paintings and a female bronze . Jawlensky saw his younger fellow countryman as a "natural", took him into care and recommended him to the art educator Knirr so he could complete the training he had begun in Moscow and continued in Venice and with Cormon in Paris. The renowned art historian Richard Reiche passed his judgment in 1912:

"It is our duty and pleasure to [.] testify to the outstanding intellectual and artistic contribution of the Russian artists in Munich to the formation and the success of the 'Neue Künstlervereinigung' at that time. [.] Bechteev and baroness Werefkin were strong elements of this union."

Important and frequent participations in exhibitions and sales of his paintings until 1914 also speak for Bechteev's position in the German art scene at that time.

First World War and return to Russia – Bechteev's retreat into graphic art

The development of progressive painting saw a sudden halt with the outbreak of World War I. Being a Russian citizen, Bechteev was immediately expelled from Germany and was forced to leave numerous pictures that occasionally appear on the art market behind. As a former cavalryman he was immediately drafted into the army, however, he was soon soon transferred to the state circus for disciplinary reasons. This gave him the fortunate opportunity to develop his style of Cubism in costume- and set designs. There is proof of his participation in the exhibition "Vom Impressionismus zur ungegenständlichen Malerei“ (From Impressionism to Abstract Painting) at the State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow in 1918/19. Unfortunately, the epoch of the Russian avant-garde‘s artistic awakening lasted only a few years. As a member of the nobility, Bechteev, along with his wife, was exiled to Siberia for eight years. While he wasn‘t able to paint in exile the ability to make drawings, now in a fine "naturalistic" manner as abstraction was simply forbidden, must have comforted him a little and his mastery as a graphic artist was met with official recognition. Back in Moscow he soon achieved great fame as illustrator of around 120 books. His drawings and watercolors were also shown in Russian museums on numerous occasions.

The art-historical appreciation of Bechteev's outstanding early work

What about today? Rediscovered, also in Russia, where the lack of early works is deeply regretted. The break marked by war I and the Iron Curtain could not be bridged, even if the number of more than 60 exhibition participations and 200 catalog entries and articles in Germany, but mostly in Russia (see Ildar Galeyev, 2005) dispel any doubt regarding Bechteev‘s importance. In 2018 a large solo exhibition was finally shown at the Murnau Castle Museum, accompanied by a beautiful catalog that impressively documents.

Jelena Hahl-Fontaine (formerly Hahl-Koch), Dr. phil. in art history and Slavic studies, former curator at the Lenbachhaus Munich, visited and interviewed Bechteev in Moscow in the 1960s. Since then she has researched and published on Bechteev, Kandinsky and the art of the "Blaue Reiter".

On the provenance – In Barmen and Dresden

Bechteev's "Leda" is not only fascinating in terms of its artistic appeal, it also has a fascinating background story. Soon after it was made in 1912, the large picture was sent to Barmen, where the local art association under Richart Reiche had become established as a vibrant center of modernity. In December 1912, Bechteev took part in an exhibition of 41 works by artists of the expressionistic "Neue Künstlervereinigung München" (New Munich Art Association, N.K.V.M.), the nucleus of the "Blaue Reiter". And as luck would have it, the Düsseldorf collector Werner Dücker (1887–1945, died as a prisoner of war) also exhibited his outstanding collection in Barmen. Eighteen paintings and one sculpture by French artists such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, but also by outstanding German painters like Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and, last but not least, Vladimir von Bechteev, were on display. Even though neither exhibition was accompanied by a catalog, it is little surprising that Dücker discovered "Leda" browsing the N.K.V.M. exhibition rooms. A little later he bought the picture directly from Kunstverein Barmen, as it is noted in its business records. In January 1914, the Dresden gallery Arnold finally presented the work in the important exhibition "Die neue Malerei" (The New Painting) organized by Richart Reiche, the first major Expressionism show in Dresden. It came as a loan from Werner Dücker, who had marked his "Leda" as ‘not for sale‘ in the catalog.

A fascinating collector

The collector Werner Dücker, a Catholic from the Rhineland, was, as far as the scanty sources indicate, a dazzling personality: wealthy and sophisticated, progressive and liberal. Dücker and his wife, the sculptress Marta Zahn, were close friends of Richard Schultz, through whom they got into contact with the lively gay scene in Berlin (cf. Karl-Heinz Steinle, der literarische Salon bei Richard Schultz, Berlin 2002). The group of friends met at literary salons, were avid nudists and followers of Adolf Koch, a luminary of nudism, and were regulars at the legendary "Westend-Klause" with the innkeeper Walter Franke's. Werner Dücker was clearly attracted by the sexual freedom and openness that modernity had to offer. And Bechteev's "Leda mit dem Schwan" is also a work with a clearly erotic appeal that is as elegant as it is succinct. It is not surprising that Werner Dücker was willing to spend the considerable sum of 1650 Reichsmark on the work in 1913.

But Dücker was not able to enjoy his "Leda" for very long. In 1923 he lost all of his fortune due to the hyperinflation. Marta then opened a fashion store to make more money than she could through sculpting, and the highly significant art collection had to be sold. Richard Schultz took over some of the works from his friend Dücker – but there is no reference to "Leda" in the Schultz estate. It was only a few decades ago that Bechteev's masterpiece – unidentified as such – reappeared in a private collection. [AT]

203

Wladimir Georgiewitsch von Bechtejeff

Leda und der Schwan, 1912.

Oil on canvas

Estimate:

€ 300,000 / $ 354,000 Sold:

€ 375,000 / $ 442,500 (incl. surcharge)

Headquarters

Joseph-Wild-Str. 18

81829 Munich

Phone: +49 89 55 244-0

Fax: +49 89 55 244-177

info@kettererkunst.de

Louisa von Saucken / Undine Schleifer

Holstenwall 5

20355 Hamburg

Phone: +49 40 37 49 61-0

Fax: +49 40 37 49 61-66

infohamburg@kettererkunst.de

Dr. Simone Wiechers / Nane Schlage

Fasanenstr. 70

10719 Berlin

Phone: +49 30 88 67 53-63

Fax: +49 30 88 67 56-43

infoberlin@kettererkunst.de

Cordula Lichtenberg

Gertrudenstraße 24-28

50667 Cologne

Phone: +49 221 510 908-15

infokoeln@kettererkunst.de

Hessen

Rhineland-Palatinate

Miriam Heß

Phone: +49 62 21 58 80-038

Fax: +49 62 21 58 80-595

infoheidelberg@kettererkunst.de

We will inform you in time.

Lot 203

Lot 203