Video

232

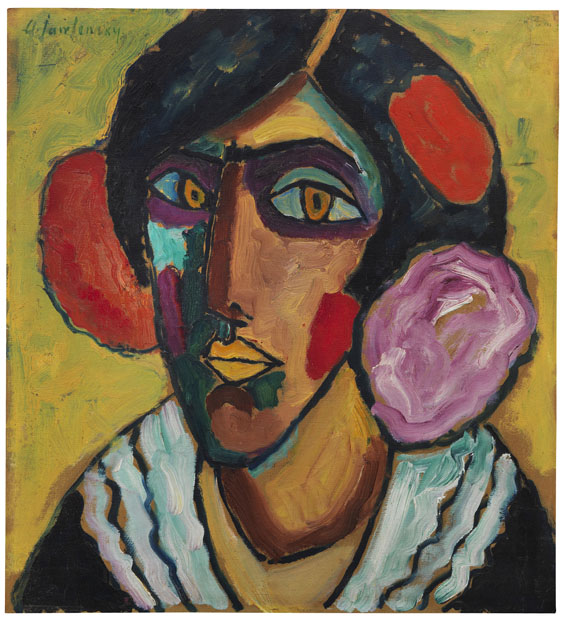

Alexej von Jawlensky

Frauenkopf mit Blumen im Haar, Um 1913.

Oil on cardboard

Estimate:

€ 2,500,000 / $ 2,950,000 Sold:

€ 2,905,000 / $ 3,427,900 (incl. surcharge)

Frauenkopf mit Blumen im Haar. Um 1913.

Oil on cardboard.

Upper left signed. Rear of the board inscribed "1. Frauenkopf mit Blumen im Haar" by Emmy "Galka" Scheyer (around 1920). Inscribed with the address "Giselastr.", with a label of Galerie Commeter in Hamburg and with an inscription by Galerie Ernst Arnold in Dresden on the reverse of the original frame. 53.5 x 49.3 cm (21 x 19.4 in).

• Sensational rediscovery. Family-owned for 100 years.

• One of the most beautiful and characterful portraits from the group of works of the 'Heads' made before the First World War.

• Bold color contrasts culminate in an expressive blaze of colors.

• No comparable work has been offered on the international auction market in the last ten years.

Accompanied by a confirmation issued by the Alexej von Jawlensky - Archive S.A., Locarno, issued on August 18, 2017.

There is a loan request for this painting from the Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle an der Saale.

For a more detailed catalog desription, please see our extra catalog.

Contact Nicola Countess Keglevich for more information:

n.keglevich@kettererkunst.de

+49(0)89 552 44 - 175.

PROVENANCE: Artist‘s studio (until 1920).

Emmy "Galka" Scheyer, Wiesbaden (in commission from the artist‘s ownership, as of 1920, with the title on the reverse).

Private collection of the government building officer H.L.V. Rhineland-Palatinate (presumably acquired in the 1920s, until 1957).

Private collection H.V. (inherited from the above in 1957, until 1976).

Private collection H.W. (since 1976, gifted from the above).

EXHIBITION: With a label of Galerie Commeter, Hamburg and an inscription by Galerie Ernst Arnold, Dresden, on the reverse of the original artist frame.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Traveling Exhibition 1920/21 (with stops in, among others, Berlin, Galerie Fritz Gurlitt; Hamburg, Galerie Commeter; Munich, Galerie Hans Goltz; Hanover, Kestner Society; Stuttgart, Württembergischer Kunstverein; Frankfurt, Kunstsalon Ludwig Schames; Wiesbaden, Neues Museum; Wuppertal-Barmen, Ruhmeshalle; Mannheim, Kunsthalle, Galerie Ernst Arnold, Dresden and others, with alternating works on display.

Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle (Saale), permanent exhibition, August 2017 - October 2021, part of the collection "Wege der Moderne. Kunst in Deutschland im 20. Jahrhundert".

LITERATURE: Galka Scheyer, Alexej von Jawlensky, ex. cat of traveling exhibition, 1920/21, there listed as, among others, Kopf 1913.

Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle (Saale), Malerei der Moderne 1900 bis 1945, vol. 20, Munich 2017, p. 50 with color illu.

Alexej von Jawlensky-Archive S.A., Locarno (editor), Bild und Wissenschaft. Forschungsbeiträge zu Leben und Werk A. v. Jawlenskys, vol. 4 (to be released in 2022).

“The 'Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair' was made in one of the artist's most important creative periods shortly before World War I. Although Jawlensky worked in an extremely powerful and expressive manner during this period, he also captured subtle moods with great sensuality. In this case it is a restrained melancholy that covers the entire picture like a pleasant veil and that makes for its special appeal. Not least because of this, the hitherto unknown painting with its passionately painted warm-red hair ornament and the billowing mint-cool collar strips can be described as an outstanding discovery."

Dr. Roman Zieglgänsberger, Museum Wiesbaden

Oil on cardboard.

Upper left signed. Rear of the board inscribed "1. Frauenkopf mit Blumen im Haar" by Emmy "Galka" Scheyer (around 1920). Inscribed with the address "Giselastr.", with a label of Galerie Commeter in Hamburg and with an inscription by Galerie Ernst Arnold in Dresden on the reverse of the original frame. 53.5 x 49.3 cm (21 x 19.4 in).

• Sensational rediscovery. Family-owned for 100 years.

• One of the most beautiful and characterful portraits from the group of works of the 'Heads' made before the First World War.

• Bold color contrasts culminate in an expressive blaze of colors.

• No comparable work has been offered on the international auction market in the last ten years.

Accompanied by a confirmation issued by the Alexej von Jawlensky - Archive S.A., Locarno, issued on August 18, 2017.

There is a loan request for this painting from the Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle an der Saale.

For a more detailed catalog desription, please see our extra catalog.

Contact Nicola Countess Keglevich for more information:

n.keglevich@kettererkunst.de

+49(0)89 552 44 - 175.

PROVENANCE: Artist‘s studio (until 1920).

Emmy "Galka" Scheyer, Wiesbaden (in commission from the artist‘s ownership, as of 1920, with the title on the reverse).

Private collection of the government building officer H.L.V. Rhineland-Palatinate (presumably acquired in the 1920s, until 1957).

Private collection H.V. (inherited from the above in 1957, until 1976).

Private collection H.W. (since 1976, gifted from the above).

EXHIBITION: With a label of Galerie Commeter, Hamburg and an inscription by Galerie Ernst Arnold, Dresden, on the reverse of the original artist frame.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Traveling Exhibition 1920/21 (with stops in, among others, Berlin, Galerie Fritz Gurlitt; Hamburg, Galerie Commeter; Munich, Galerie Hans Goltz; Hanover, Kestner Society; Stuttgart, Württembergischer Kunstverein; Frankfurt, Kunstsalon Ludwig Schames; Wiesbaden, Neues Museum; Wuppertal-Barmen, Ruhmeshalle; Mannheim, Kunsthalle, Galerie Ernst Arnold, Dresden and others, with alternating works on display.

Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle (Saale), permanent exhibition, August 2017 - October 2021, part of the collection "Wege der Moderne. Kunst in Deutschland im 20. Jahrhundert".

LITERATURE: Galka Scheyer, Alexej von Jawlensky, ex. cat of traveling exhibition, 1920/21, there listed as, among others, Kopf 1913.

Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle (Saale), Malerei der Moderne 1900 bis 1945, vol. 20, Munich 2017, p. 50 with color illu.

Alexej von Jawlensky-Archive S.A., Locarno (editor), Bild und Wissenschaft. Forschungsbeiträge zu Leben und Werk A. v. Jawlenskys, vol. 4 (to be released in 2022).

“The 'Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair' was made in one of the artist's most important creative periods shortly before World War I. Although Jawlensky worked in an extremely powerful and expressive manner during this period, he also captured subtle moods with great sensuality. In this case it is a restrained melancholy that covers the entire picture like a pleasant veil and that makes for its special appeal. Not least because of this, the hitherto unknown painting with its passionately painted warm-red hair ornament and the billowing mint-cool collar strips can be described as an outstanding discovery."

Dr. Roman Zieglgänsberger, Museum Wiesbaden

Research

An examination of the decorative frame of “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” has revealed that it is the original artist's frame from the artist's apartment. The address on "Giselastr." - Jawlensky's studio/apartment until 1920 - was inscribed in Sütterlin script in pencil on the lower bar by a hand other than that of the artist. A label of the Hamburg gallery Commeter also refers to the traveling exhibition organized by Galka Scheyer for the years 1920/21. In addition, it is inscribed with a sequence of numbers and an abbreviation in grease crayon. Our provenance research department assigns this inscription to the Dresden gallery Ernst Arnold. Follow-up research finally provided proof that above-mentioned traveling exhibition actually stopped at this gallery in April 1921: The monthly magazine “Das Kunstblatt”, published by Paul Westheim, advertised the exhibition "Jawlensky" at its premises in April 1921, issue 4, p. 127. This closes the previous gap in the exhibition history of the traveling exhibition between the stops in Barmen (March 1921) and the stop in Düsseldorf (May / early June 1921).

Jawlensky and the portrait

The human head is Jawlensky's main subject, with which them he had developed his novel, expressive style before World War I. The portraits made before 1914 laid the foundations for his fame and count among his most sought-after and most popular works today, just as they did during the artist's lifetime. In these bright and expressive heads, Jawlensky seemed to do without individualized effigies while reconceiving a stylized monumentality: The heads he subjected to his radical presentation show physiognomies that come from his self-developed ‘model kit’, with magically attractive eyes, strong brows, emphasized nasal bridges, line-like framed mouths, accentuated hairlines and brightly colored cheeks: “broad composition of pure and energetic colors, which are particularly enhanced through their harmony with the graphic form”, as Kandinsky described it so tellingly (quoted from: Annegret Hoberg, Jawlensky und Werefkin - Im Kreis der Neuen Künstlervereinigung München und des Blauen Reiters, in: Lebensmenschen - Alexej von Jawlensky und Marianne von Werefkin, Munich 2019, pp. 200-220, here p. 203).

In the summer of 1911 Jawlensky traveled to Prerow on the Baltic Sea and, as he later recalled, painted “my best landscapes and large figural works in very strong, glowing colors, absolutely not naturalistic. I took a lot of red, blue, orange, cadmium yellow, chromium oxide green. The forms were strongly contoured in Prussian blue and emanated strength from an inner ecstasy ”(quoted from: ex. cat. Alexej von Jawlensky. Reisen, Freunde, Wandlungen, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund, 1998, p. 114).

Jawlensky gave the portraits he presumably painted in Prerow on the Baltic Sea titles like “Helene mit blauem Turban“ (Helene with a Blue Turban) “Blonde Frau“ (Blonde woman), “Bucklige“ (Hunchback), “Russin“ (Russian Woman), “Frau mit roter Bluse“ (Woman with a red Blouse). It is not known whether the artist actually encountered the models for his “figurale Figuren“ (figural figures) after his return to Munich, or whether he conceived them from a sort of ‘prototype head‘ and gave the variations of the diverse characters specific titles. Many of the heads, mostly female and at times with a certain male appearance, were not intended as individualized portraits, but, as their titles suggest, portraits of ‘exotic‘ types from distant cultures: "Asiatin" (Asian), "Französin" (French Woman), “Frau aus Turkmenistan (Woman from Turkestan)“, “Sizilianerin mit grünem Schal“ (Sicilian Woman with a green Scarf), “Spanisches Mächen“ (Spanish Girl), “Kreolische Frau“ (Creole Woman), “Byzantinische Frau” (Byzantine Woman) or “Ägyptische Frau“ (Egyptian Woman), “Barbarenfürstin” (Barbarian Princess). These are expressive, iconic portraits that testify to Jawlensky's attempt, beginning around 1911, to abstract from the individual to the general, to standardize the shape of the heads, while at the same time to embellish the motif in a painterly and narrative manner.

A mystical key picture

When comparing “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” with these expressive from a little earlier, the enormous step Jawlensky made in 1913 becomes particularly evident. “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” is a key picture within this remarkable artistic development, which Karl Schmidt-Rottluff appropriately summed up for Jawlensky in 1934: “I confess my admiration for the work you have created over the years, beginning with the strong, sanguine colors, and which you expanded to the quiet, spiritual images that I would like to call truly modern pictures of saints. It seems to me that in them an old Russian icon painter has been reawakened - so real and devotional and absorbed, as there is nothing like it today. ”(Quoted from: Roman Zieglgänsberger, Alexej von Jawlensky, Cologne 2016, p. 4).

“Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” clearly visualizes where this “new” came from. Jawlensky combined his obvious liking for Eastern mysticism and religiousness with his meanwhile pronounced expressive painting style. Richart Reiche, who showed a comprehensive Jawlensky exhibition at the Ruhmenshalle Barmen in late 1921, recognized how much the artist was influenced by Byzantine imagery (Feuer: Monatsschrift für Kunst und künstlerische Kultur, 3.1921/1922, p. 27). How obvious this assumption is, especially in the case of "Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair", is not only shown by the painting itself with its hint of an Eastern Christian "gold ground".

Masquerades and models

What is striking about the portrait “Woman's Head with Flowers in Her Hair” is, not least, the decor: three large, lush flowers, perhaps peonies, adorn the sitter‘s black, severely parted hair. The black dress is trimmed with a light lace collar. This combination of flowers and lace is well known: As of 1911, Jawlensky used it particularly often in the group of works with the new motif of the “Spanierin“ (Spaniard). Perhaps it is not even a female model but the dancer Alexander Sacharoff, who already posed for the “Spaniards”, as Elisabeth Erdmann-Macke said: Back then he painted large-format pictures in strong colors, many of them showing the dancer Sacharoff, whom he disguised as a woman and Spaniard with a fan and mantilla. (Quoted from: Elisabeth Erdmann-Macke, Erinnerung an August Macke, Stuttgart 1962, p. 191). This discovery, explicitly described by a contemporary witness, renders further fantasies possible and allows for the assumption that the artist took a similar approach to the portrait “Woman's Head with Flowers in Her Hair”. From the beginning of 1905, Jawlensky and Sacharoff developed a close friendship. Born in the Ukraine, he studied painting in Paris in 1903/04, and then studied dancing in Munich. In 1910, Sacharoff performed his first sensational expressive dances in self-designed costumes at the Munich Odeon. According to the art historian Annegret Hoberg, an expert on the Munich art scene before World War I, Sacharoff, alongside Helene Nesnakomoff, the mother of Jawlensky's son Andreas, was his favorite model. Both posed for the expressive portraits and colorful heads, which made for the key genre of his pre-war painting: “The costumed and rouged dancer Sacharoff also posed for numerous other 'female' portraits up to 1913, such as the 'Spaniard', while Helene turned into an Asian or a barbarian princess and the portraits of, for example, Turandot I, were entirely independent of a real model. (Annegret Hoberg, quoted from: Lebensmenschen - Alexej von Jawlensky und Marianne von Werefkin, Munich 2019, p. 207). The painter was particularly fascinated by the intense gaze of the androgynous dancer. He let the dancer slip into roles that suited his expressive mentality. As early as in 1909, Sacharoff was the protagonist in Jawlensky's greatest paintings, among them “Bildnis des Tänzers Alexander Sacharoff“ (Portrait of the Dancer Alexander Sacharoff) with a face in white make-up and a vermilion costume. In the painting “Die weiße Feder“ (The White Feather) the dancer mimes a Japanese woman in an imaginative costume, while in “Rote Lippen“ (Red Lips), the painter shows the dancer in a highly erotic gesture . Three paintings in which Jawlensky did not only render homage to the art of disguising the dancer between the sexes, but through which he also discovered his versatile facial play as a motif for his portrait world.

Jawlensky and Lola Montez

In the important years before World War I, Jawlensky was particularly open-minded and had a genuine ability to process the most diverse impulses without prejudice and transformed them into his own. Jawlensky soaked up a wide variety of inspirations like a sponge during these years, and - in a much different way - one of these inspirations seems to have been the scandalous story of Lola Montez. Reflections of her can unmistakably found in the portrait “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair”; and they once more show the impressive complexity of this painting. It's a story that testifies to Jawlensky's penchant for the bizarre. Lulu, as friends called the painter in reference to the bawdy protagonist in Frank Wedekind's “Earth Spirit”, ultimately loved women as much as he loved masquerade, theater, dance, mystery and scandal. An occurrence with a comparable lewdness and the talk of Schwabing around the time when “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” was made, and which certainly did not escape the artist‘s attention, was the scandal around Lola Montez. Elizabeth Rosanna Gilbert, known as Lola Montez, was an urbane impostor who, as the scandalous mistress of Ludwig I, became a political millstone. Since the beginning of the 1840s she had passed herself off as a Spanish dancer from Seville, first in London and later in Munich.

1911, the year Jawlensky began to paint the series "Spaniards", marked the 50th anniversary of her death. The following year, 1912, Richard Bong's Berlin publishing house released the historical novel “Lola Montez” by the Austrian writer Joseph August Lux, its print run soon exceeded 30 thousand copies. This great success also must have been of interest in the circle around Jawlensky, not least because Lux, who was closely connected with the “Werkbund”, just like Jawlensky, was part of the “Schwabing Bohème”. He had lived in Munich since 1910, and in 1913 he moved from Lehel to Adelheidstrasse 35 in Schwabing. It seems obvious that the two at least knew each other by sight. Lux did not describe Lola Montez as the scandalous laughingstock that she had long been caricatured as, and also painted a different picture of her than Josef Ruederer did in his political comedy “Die Morgenröte”. When the play premiered in Munich, a critic from the “Allgemeine Zeitung” wrote on March 15, 1913, that Ruederer vilified Lola to a “prostitute of the lowest rank”. For Lux, the Montez is more like a "sphinx" (Joseph August Lux, Lola Montez, ein historischer Roman, Berlin 1912, pp. 158, 260), a mysterious and elusive hybrid creature: “A holy-beautiful peccability, a wicked saint, a mixture of woman and child, of hetaera and virgin, wanton and madonna-like, demure, daring and fearful, [...], vicious and honorable, selfish, selfless and devoted [...] - no surprise that men murdered each other because of her ”( Lux, Lola Montez, p. 3).

Around 1912/13 the enormous presence of a 60-year-old scandal certainly did not escape the attention of the “Giselists”, the circle around Werefkin and Jawlensky who had a salon on Giselastraße 23, and it was probably no coincidence that Jawlensky even called one of the “Spaniards” “Lola”. Sure, the entire habitus of these Spanish women, with lace veils and flowers in black hair, with penetrating gaze, is what Jawlensky's group of works have in common with Lola Montez, who coined this type for a long time and still does today.

Stieler characterized the strict and at the same time mysterious, seductive-looking person with a striking white lace collar over a tight, black dress - a standard in Spanish court painting under Velázquez - with just a touch of a black veil covering the hair, and, in addition to other decorative details, finding completion with the striking red flowers tucked into her straightened hair. Juxtaposing this portrait of Montez with Jawlensky's "Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair", the analogy becomes quite obvious. And that applies not only to the attributes, but also to the peculiar and bright blue of the melancholic eyes in contrast to the black hair, which may remind of what was said about the magical gaze of Lola Montez: “The big, melancholic eyes emanate a blue shine; it seemed like no one but her had eyes: those blue-looking [sic] eyes that could bewitch.” (Lux, Lola Montez, p. 7).

The flight

When World War I broke out, the Russians Jawlensky and Werefkin, living in exile in Munich, were officially declared members of an "enemy state". Head over heels, within just 48 hours, they had to flee and leave everything behind on Giselastrasse. As of the autumn of 1914, Lily Klee and the painter Adolf Erbslöh took care of the apartment. But what happened with the numerous works of art that Jawlensky had to leave behind in 1914? At this point, another important woman in his life entered the stage: Emmy 'Galka' Scheyer.

The agent

Emmy Scheyer, daughter of a Brunswick canning manufacturer, met Alexej von Jawlensky in Lausanne on the occasion of an exhibition in 1916. She was a 27-year-old art student, he a 52-year-old painter who later nicknamed her “Galka” (jackdaw). Enthusiastic about Jawlensky's painting “Der Buckel“ (The Hump), she decided to give up her own painting career and instead began to focus on the professional marketing of Jawlensky's works, investing in exhibitions and publications, sales and negotiations. A contract set up between Galka Scheyer and Alexej von Jawlensky covered all details. Galka Scheyer visited Munich for the first time in 1919, went to the apartment on Giselastraße and inspected the works of art that had been left behind. After the apartment had been liquidated in 1920, the boxes with the paintings were stored with Emmy Scheyer, who lived with her parents in Brunswick again.

“Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” and the traveling exhibition

Soon after a first inspection and full of energy, Galka Scheyer planned to bring back memories of Jawlensky's work to the public with the help of a grand traveling exhibition through Germany. With great enthusiasm she reported to Jawlensky how she unpacked the pictures, arranging them in groups and either putting labels with titles on their backs or writing directly on them, and she also wanted to frame the works. Galka Scheyer inscribed the back of our work: “A. von Jawlensky ”and: “1. Frauenkopf. mit Blumen im Haar“, whereby the addition “mit Blumen im haar“ (with flowers in the hair) was probably added later.

It was also mounted in a new frame that Scheyer had taken from Jawlensky's apartment. This frame, in which the work “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” has remained tothis day, is not only inscribed with the address “Giselastr.” in Sütterlin script, but also bears evidence of two stations of the widely-noticed traveling exhibition, in which this work was also shown. One label comes from Galerie Commeter in Hamburg, and it also carries an inscription in grease crayon from Galerie Arnold in Dresden - both were locations where the traveling exhibition was shown. Apparently, as research had not been aware of, the tour also had a stop at the Dresden gallery Arnold. In any case, the magazine “Das Kunstblatt” advertised the exhibition “Jawlensky” at its premises in April 1921, issue 4, p. 127.

Two different catalogs of the traveling exhibition are known, one comprising 100, the other 136 lots. Information on the list of works is so rudimentary that an unequivocal assignment of individual paintings is only possible in very few cases. In addition, the compilation of works on display changed from stop to stop. Galka Scheyer made the selection of works to be exhibited in coordination with the respective exhibition stations, and, depending on sales, supplemented them with further paintings. Accordingly, she went to Frankfurt in person and visited the gallery owner Ludwig Schames, made contact with Paul Erich Küppers in Hanover, the director of the Kestner Society founded in 1916, and negotiated with Richart Reiche, head of the ‘Ruhmeshalle‘ in Barmen (Wuppertal). However, the traveling exhibition would commence at Fritz Gurlitt's gallery in Berlin in the summer of 1920. After various stations, it also celebrated a great success in Wiesbaden, about which Scheyer reported to Jawlensky: "20 pictures sold, 2 still in negotiation ... Almost all of them were bought from the reserve", which means that they were not in the catalog! Jawlensky is deeply grateful to her and thanked Emmy Scheyer on April 21, 1921: "I have put my art in your hands and will do everything to show you that I want to live and go further and further". And a few days later, on April 27, the artist expressed: “God and fate gave me you, Emmy, on my way. And I'm so grateful for everything you do for me. God will reward you.”(Quoted from: Angelica Jawlensky, in: ex. cat. Die Blaue Vier, Bern, 1997, p. 70)

Provenance. A rediscovered masterpiece

At what point Jawlensky's “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” changed owners after the grand exhibition tour can not be identified with certainty today. The buyer was an architect working in the style of “New Objectivity” in the area of housing development in the 1920s. Many of his buildings have been preserved up until today, and find mention in the “Denkmaltopographie der Bundesrepublik Deutschland“ (Monument Topography of the Federal Republic of Germany). Perhaps he also attended the artist's first solo exhibition at the Barmen ‘Ruhmeshalle‘ in 1911 - at that time the architect was working in the immediate vicinity. He later settled in the Frankfurt area, where he implemented his modernist ideas in the style of “ New Objectivity“ in his own villa in the late 1920s. One can vividly imagine how deeply touching the spiritual work “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” must have looked in this ambiance.

“Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” always remained within the family through inheritance and endowments. This may be the reason why this painting was not known to Clemens Weiler, author of the first catalog raisonné, and that it had not been recorded with the Jawlensky Archive before 2017. Accordingly, the wonderful rediscovery of the painting “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” is a little sensation. The fact that we are now able to get to know this great work of art together is a great enrichment to art history. “Those lucky enough to call a picture by Jawlensky their own, I recommend to keep it covered with a curtain, and to only indulge in its impression at special moments. They want to be observed like the most precious pictures of saints in the shrines of the old winged altars. They should only appear on festive days. ”(W. A. ??Luz, A. von Jawlensky. Neue Bildnisse, in: Der Cicerone: Halbmontatsschrift für die Interessen des Kunstforschers & Sammlers 13.1921, pp. 684–689, here p. 689)

Dr. Mario von Lüttichau, Dr. Agnes Thum

Quote:

“The painting 'Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair' was made in one of the artist's most important creative periods shortly before World War I. Although Jawlensky worked in an extremely powerful and expressive manner during this period, he also captured subtle moods with great sensuality. In this case it is a restrained melancholy that covers the entire picture like a pleasant veil and that makes for its special appeal. Not least because of this, the hitherto unknown painting with its passionately painted warm-red hair ornament and the billowing mint-cool collar strips can be described as an outstanding discovery.“

Dr. Roman Zieglgänsberger, Museum Wiesbaden

An examination of the decorative frame of “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” has revealed that it is the original artist's frame from the artist's apartment. The address on "Giselastr." - Jawlensky's studio/apartment until 1920 - was inscribed in Sütterlin script in pencil on the lower bar by a hand other than that of the artist. A label of the Hamburg gallery Commeter also refers to the traveling exhibition organized by Galka Scheyer for the years 1920/21. In addition, it is inscribed with a sequence of numbers and an abbreviation in grease crayon. Our provenance research department assigns this inscription to the Dresden gallery Ernst Arnold. Follow-up research finally provided proof that above-mentioned traveling exhibition actually stopped at this gallery in April 1921: The monthly magazine “Das Kunstblatt”, published by Paul Westheim, advertised the exhibition "Jawlensky" at its premises in April 1921, issue 4, p. 127. This closes the previous gap in the exhibition history of the traveling exhibition between the stops in Barmen (March 1921) and the stop in Düsseldorf (May / early June 1921).

Jawlensky and the portrait

The human head is Jawlensky's main subject, with which them he had developed his novel, expressive style before World War I. The portraits made before 1914 laid the foundations for his fame and count among his most sought-after and most popular works today, just as they did during the artist's lifetime. In these bright and expressive heads, Jawlensky seemed to do without individualized effigies while reconceiving a stylized monumentality: The heads he subjected to his radical presentation show physiognomies that come from his self-developed ‘model kit’, with magically attractive eyes, strong brows, emphasized nasal bridges, line-like framed mouths, accentuated hairlines and brightly colored cheeks: “broad composition of pure and energetic colors, which are particularly enhanced through their harmony with the graphic form”, as Kandinsky described it so tellingly (quoted from: Annegret Hoberg, Jawlensky und Werefkin - Im Kreis der Neuen Künstlervereinigung München und des Blauen Reiters, in: Lebensmenschen - Alexej von Jawlensky und Marianne von Werefkin, Munich 2019, pp. 200-220, here p. 203).

In the summer of 1911 Jawlensky traveled to Prerow on the Baltic Sea and, as he later recalled, painted “my best landscapes and large figural works in very strong, glowing colors, absolutely not naturalistic. I took a lot of red, blue, orange, cadmium yellow, chromium oxide green. The forms were strongly contoured in Prussian blue and emanated strength from an inner ecstasy ”(quoted from: ex. cat. Alexej von Jawlensky. Reisen, Freunde, Wandlungen, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund, 1998, p. 114).

Jawlensky gave the portraits he presumably painted in Prerow on the Baltic Sea titles like “Helene mit blauem Turban“ (Helene with a Blue Turban) “Blonde Frau“ (Blonde woman), “Bucklige“ (Hunchback), “Russin“ (Russian Woman), “Frau mit roter Bluse“ (Woman with a red Blouse). It is not known whether the artist actually encountered the models for his “figurale Figuren“ (figural figures) after his return to Munich, or whether he conceived them from a sort of ‘prototype head‘ and gave the variations of the diverse characters specific titles. Many of the heads, mostly female and at times with a certain male appearance, were not intended as individualized portraits, but, as their titles suggest, portraits of ‘exotic‘ types from distant cultures: "Asiatin" (Asian), "Französin" (French Woman), “Frau aus Turkmenistan (Woman from Turkestan)“, “Sizilianerin mit grünem Schal“ (Sicilian Woman with a green Scarf), “Spanisches Mächen“ (Spanish Girl), “Kreolische Frau“ (Creole Woman), “Byzantinische Frau” (Byzantine Woman) or “Ägyptische Frau“ (Egyptian Woman), “Barbarenfürstin” (Barbarian Princess). These are expressive, iconic portraits that testify to Jawlensky's attempt, beginning around 1911, to abstract from the individual to the general, to standardize the shape of the heads, while at the same time to embellish the motif in a painterly and narrative manner.

A mystical key picture

When comparing “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” with these expressive from a little earlier, the enormous step Jawlensky made in 1913 becomes particularly evident. “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” is a key picture within this remarkable artistic development, which Karl Schmidt-Rottluff appropriately summed up for Jawlensky in 1934: “I confess my admiration for the work you have created over the years, beginning with the strong, sanguine colors, and which you expanded to the quiet, spiritual images that I would like to call truly modern pictures of saints. It seems to me that in them an old Russian icon painter has been reawakened - so real and devotional and absorbed, as there is nothing like it today. ”(Quoted from: Roman Zieglgänsberger, Alexej von Jawlensky, Cologne 2016, p. 4).

“Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” clearly visualizes where this “new” came from. Jawlensky combined his obvious liking for Eastern mysticism and religiousness with his meanwhile pronounced expressive painting style. Richart Reiche, who showed a comprehensive Jawlensky exhibition at the Ruhmenshalle Barmen in late 1921, recognized how much the artist was influenced by Byzantine imagery (Feuer: Monatsschrift für Kunst und künstlerische Kultur, 3.1921/1922, p. 27). How obvious this assumption is, especially in the case of "Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair", is not only shown by the painting itself with its hint of an Eastern Christian "gold ground".

Masquerades and models

What is striking about the portrait “Woman's Head with Flowers in Her Hair” is, not least, the decor: three large, lush flowers, perhaps peonies, adorn the sitter‘s black, severely parted hair. The black dress is trimmed with a light lace collar. This combination of flowers and lace is well known: As of 1911, Jawlensky used it particularly often in the group of works with the new motif of the “Spanierin“ (Spaniard). Perhaps it is not even a female model but the dancer Alexander Sacharoff, who already posed for the “Spaniards”, as Elisabeth Erdmann-Macke said: Back then he painted large-format pictures in strong colors, many of them showing the dancer Sacharoff, whom he disguised as a woman and Spaniard with a fan and mantilla. (Quoted from: Elisabeth Erdmann-Macke, Erinnerung an August Macke, Stuttgart 1962, p. 191). This discovery, explicitly described by a contemporary witness, renders further fantasies possible and allows for the assumption that the artist took a similar approach to the portrait “Woman's Head with Flowers in Her Hair”. From the beginning of 1905, Jawlensky and Sacharoff developed a close friendship. Born in the Ukraine, he studied painting in Paris in 1903/04, and then studied dancing in Munich. In 1910, Sacharoff performed his first sensational expressive dances in self-designed costumes at the Munich Odeon. According to the art historian Annegret Hoberg, an expert on the Munich art scene before World War I, Sacharoff, alongside Helene Nesnakomoff, the mother of Jawlensky's son Andreas, was his favorite model. Both posed for the expressive portraits and colorful heads, which made for the key genre of his pre-war painting: “The costumed and rouged dancer Sacharoff also posed for numerous other 'female' portraits up to 1913, such as the 'Spaniard', while Helene turned into an Asian or a barbarian princess and the portraits of, for example, Turandot I, were entirely independent of a real model. (Annegret Hoberg, quoted from: Lebensmenschen - Alexej von Jawlensky und Marianne von Werefkin, Munich 2019, p. 207). The painter was particularly fascinated by the intense gaze of the androgynous dancer. He let the dancer slip into roles that suited his expressive mentality. As early as in 1909, Sacharoff was the protagonist in Jawlensky's greatest paintings, among them “Bildnis des Tänzers Alexander Sacharoff“ (Portrait of the Dancer Alexander Sacharoff) with a face in white make-up and a vermilion costume. In the painting “Die weiße Feder“ (The White Feather) the dancer mimes a Japanese woman in an imaginative costume, while in “Rote Lippen“ (Red Lips), the painter shows the dancer in a highly erotic gesture . Three paintings in which Jawlensky did not only render homage to the art of disguising the dancer between the sexes, but through which he also discovered his versatile facial play as a motif for his portrait world.

Jawlensky and Lola Montez

In the important years before World War I, Jawlensky was particularly open-minded and had a genuine ability to process the most diverse impulses without prejudice and transformed them into his own. Jawlensky soaked up a wide variety of inspirations like a sponge during these years, and - in a much different way - one of these inspirations seems to have been the scandalous story of Lola Montez. Reflections of her can unmistakably found in the portrait “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair”; and they once more show the impressive complexity of this painting. It's a story that testifies to Jawlensky's penchant for the bizarre. Lulu, as friends called the painter in reference to the bawdy protagonist in Frank Wedekind's “Earth Spirit”, ultimately loved women as much as he loved masquerade, theater, dance, mystery and scandal. An occurrence with a comparable lewdness and the talk of Schwabing around the time when “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” was made, and which certainly did not escape the artist‘s attention, was the scandal around Lola Montez. Elizabeth Rosanna Gilbert, known as Lola Montez, was an urbane impostor who, as the scandalous mistress of Ludwig I, became a political millstone. Since the beginning of the 1840s she had passed herself off as a Spanish dancer from Seville, first in London and later in Munich.

1911, the year Jawlensky began to paint the series "Spaniards", marked the 50th anniversary of her death. The following year, 1912, Richard Bong's Berlin publishing house released the historical novel “Lola Montez” by the Austrian writer Joseph August Lux, its print run soon exceeded 30 thousand copies. This great success also must have been of interest in the circle around Jawlensky, not least because Lux, who was closely connected with the “Werkbund”, just like Jawlensky, was part of the “Schwabing Bohème”. He had lived in Munich since 1910, and in 1913 he moved from Lehel to Adelheidstrasse 35 in Schwabing. It seems obvious that the two at least knew each other by sight. Lux did not describe Lola Montez as the scandalous laughingstock that she had long been caricatured as, and also painted a different picture of her than Josef Ruederer did in his political comedy “Die Morgenröte”. When the play premiered in Munich, a critic from the “Allgemeine Zeitung” wrote on March 15, 1913, that Ruederer vilified Lola to a “prostitute of the lowest rank”. For Lux, the Montez is more like a "sphinx" (Joseph August Lux, Lola Montez, ein historischer Roman, Berlin 1912, pp. 158, 260), a mysterious and elusive hybrid creature: “A holy-beautiful peccability, a wicked saint, a mixture of woman and child, of hetaera and virgin, wanton and madonna-like, demure, daring and fearful, [...], vicious and honorable, selfish, selfless and devoted [...] - no surprise that men murdered each other because of her ”( Lux, Lola Montez, p. 3).

Around 1912/13 the enormous presence of a 60-year-old scandal certainly did not escape the attention of the “Giselists”, the circle around Werefkin and Jawlensky who had a salon on Giselastraße 23, and it was probably no coincidence that Jawlensky even called one of the “Spaniards” “Lola”. Sure, the entire habitus of these Spanish women, with lace veils and flowers in black hair, with penetrating gaze, is what Jawlensky's group of works have in common with Lola Montez, who coined this type for a long time and still does today.

Stieler characterized the strict and at the same time mysterious, seductive-looking person with a striking white lace collar over a tight, black dress - a standard in Spanish court painting under Velázquez - with just a touch of a black veil covering the hair, and, in addition to other decorative details, finding completion with the striking red flowers tucked into her straightened hair. Juxtaposing this portrait of Montez with Jawlensky's "Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair", the analogy becomes quite obvious. And that applies not only to the attributes, but also to the peculiar and bright blue of the melancholic eyes in contrast to the black hair, which may remind of what was said about the magical gaze of Lola Montez: “The big, melancholic eyes emanate a blue shine; it seemed like no one but her had eyes: those blue-looking [sic] eyes that could bewitch.” (Lux, Lola Montez, p. 7).

The flight

When World War I broke out, the Russians Jawlensky and Werefkin, living in exile in Munich, were officially declared members of an "enemy state". Head over heels, within just 48 hours, they had to flee and leave everything behind on Giselastrasse. As of the autumn of 1914, Lily Klee and the painter Adolf Erbslöh took care of the apartment. But what happened with the numerous works of art that Jawlensky had to leave behind in 1914? At this point, another important woman in his life entered the stage: Emmy 'Galka' Scheyer.

The agent

Emmy Scheyer, daughter of a Brunswick canning manufacturer, met Alexej von Jawlensky in Lausanne on the occasion of an exhibition in 1916. She was a 27-year-old art student, he a 52-year-old painter who later nicknamed her “Galka” (jackdaw). Enthusiastic about Jawlensky's painting “Der Buckel“ (The Hump), she decided to give up her own painting career and instead began to focus on the professional marketing of Jawlensky's works, investing in exhibitions and publications, sales and negotiations. A contract set up between Galka Scheyer and Alexej von Jawlensky covered all details. Galka Scheyer visited Munich for the first time in 1919, went to the apartment on Giselastraße and inspected the works of art that had been left behind. After the apartment had been liquidated in 1920, the boxes with the paintings were stored with Emmy Scheyer, who lived with her parents in Brunswick again.

“Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” and the traveling exhibition

Soon after a first inspection and full of energy, Galka Scheyer planned to bring back memories of Jawlensky's work to the public with the help of a grand traveling exhibition through Germany. With great enthusiasm she reported to Jawlensky how she unpacked the pictures, arranging them in groups and either putting labels with titles on their backs or writing directly on them, and she also wanted to frame the works. Galka Scheyer inscribed the back of our work: “A. von Jawlensky ”and: “1. Frauenkopf. mit Blumen im Haar“, whereby the addition “mit Blumen im haar“ (with flowers in the hair) was probably added later.

It was also mounted in a new frame that Scheyer had taken from Jawlensky's apartment. This frame, in which the work “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” has remained tothis day, is not only inscribed with the address “Giselastr.” in Sütterlin script, but also bears evidence of two stations of the widely-noticed traveling exhibition, in which this work was also shown. One label comes from Galerie Commeter in Hamburg, and it also carries an inscription in grease crayon from Galerie Arnold in Dresden - both were locations where the traveling exhibition was shown. Apparently, as research had not been aware of, the tour also had a stop at the Dresden gallery Arnold. In any case, the magazine “Das Kunstblatt” advertised the exhibition “Jawlensky” at its premises in April 1921, issue 4, p. 127.

Two different catalogs of the traveling exhibition are known, one comprising 100, the other 136 lots. Information on the list of works is so rudimentary that an unequivocal assignment of individual paintings is only possible in very few cases. In addition, the compilation of works on display changed from stop to stop. Galka Scheyer made the selection of works to be exhibited in coordination with the respective exhibition stations, and, depending on sales, supplemented them with further paintings. Accordingly, she went to Frankfurt in person and visited the gallery owner Ludwig Schames, made contact with Paul Erich Küppers in Hanover, the director of the Kestner Society founded in 1916, and negotiated with Richart Reiche, head of the ‘Ruhmeshalle‘ in Barmen (Wuppertal). However, the traveling exhibition would commence at Fritz Gurlitt's gallery in Berlin in the summer of 1920. After various stations, it also celebrated a great success in Wiesbaden, about which Scheyer reported to Jawlensky: "20 pictures sold, 2 still in negotiation ... Almost all of them were bought from the reserve", which means that they were not in the catalog! Jawlensky is deeply grateful to her and thanked Emmy Scheyer on April 21, 1921: "I have put my art in your hands and will do everything to show you that I want to live and go further and further". And a few days later, on April 27, the artist expressed: “God and fate gave me you, Emmy, on my way. And I'm so grateful for everything you do for me. God will reward you.”(Quoted from: Angelica Jawlensky, in: ex. cat. Die Blaue Vier, Bern, 1997, p. 70)

Provenance. A rediscovered masterpiece

At what point Jawlensky's “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” changed owners after the grand exhibition tour can not be identified with certainty today. The buyer was an architect working in the style of “New Objectivity” in the area of housing development in the 1920s. Many of his buildings have been preserved up until today, and find mention in the “Denkmaltopographie der Bundesrepublik Deutschland“ (Monument Topography of the Federal Republic of Germany). Perhaps he also attended the artist's first solo exhibition at the Barmen ‘Ruhmeshalle‘ in 1911 - at that time the architect was working in the immediate vicinity. He later settled in the Frankfurt area, where he implemented his modernist ideas in the style of “ New Objectivity“ in his own villa in the late 1920s. One can vividly imagine how deeply touching the spiritual work “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” must have looked in this ambiance.

“Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” always remained within the family through inheritance and endowments. This may be the reason why this painting was not known to Clemens Weiler, author of the first catalog raisonné, and that it had not been recorded with the Jawlensky Archive before 2017. Accordingly, the wonderful rediscovery of the painting “Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair” is a little sensation. The fact that we are now able to get to know this great work of art together is a great enrichment to art history. “Those lucky enough to call a picture by Jawlensky their own, I recommend to keep it covered with a curtain, and to only indulge in its impression at special moments. They want to be observed like the most precious pictures of saints in the shrines of the old winged altars. They should only appear on festive days. ”(W. A. ??Luz, A. von Jawlensky. Neue Bildnisse, in: Der Cicerone: Halbmontatsschrift für die Interessen des Kunstforschers & Sammlers 13.1921, pp. 684–689, here p. 689)

Dr. Mario von Lüttichau, Dr. Agnes Thum

Quote:

“The painting 'Woman's Head with Flowers in her Hair' was made in one of the artist's most important creative periods shortly before World War I. Although Jawlensky worked in an extremely powerful and expressive manner during this period, he also captured subtle moods with great sensuality. In this case it is a restrained melancholy that covers the entire picture like a pleasant veil and that makes for its special appeal. Not least because of this, the hitherto unknown painting with its passionately painted warm-red hair ornament and the billowing mint-cool collar strips can be described as an outstanding discovery.“

Dr. Roman Zieglgänsberger, Museum Wiesbaden

232

Alexej von Jawlensky

Frauenkopf mit Blumen im Haar, Um 1913.

Oil on cardboard

Estimate:

€ 2,500,000 / $ 2,950,000 Sold:

€ 2,905,000 / $ 3,427,900 (incl. surcharge)

Headquarters

Joseph-Wild-Str. 18

81829 Munich

Phone: +49 89 55 244-0

Fax: +49 89 55 244-177

info@kettererkunst.de

Louisa von Saucken / Undine Schleifer

Holstenwall 5

20355 Hamburg

Phone: +49 40 37 49 61-0

Fax: +49 40 37 49 61-66

infohamburg@kettererkunst.de

Dr. Simone Wiechers / Nane Schlage

Fasanenstr. 70

10719 Berlin

Phone: +49 30 88 67 53-63

Fax: +49 30 88 67 56-43

infoberlin@kettererkunst.de

Cordula Lichtenberg

Gertrudenstraße 24-28

50667 Cologne

Phone: +49 221 510 908-15

infokoeln@kettererkunst.de

Hessen

Rhineland-Palatinate

Miriam Heß

Phone: +49 62 21 58 80-038

Fax: +49 62 21 58 80-595

infoheidelberg@kettererkunst.de

We will inform you in time.

Lot 232

Lot 232