Frame image

38

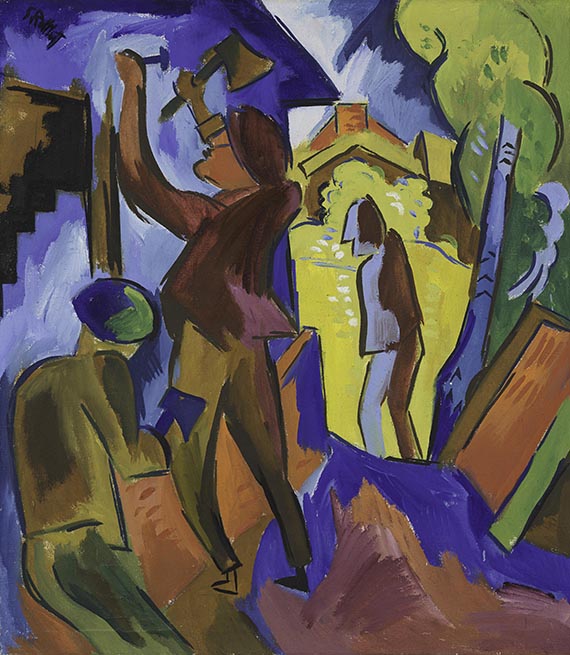

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

Scheune (Jershöft), 1921.

Oil on canvas

Estimate:

€ 300,000 / $ 339,000 Sold:

€ 558,800 / $ 631,443 (incl. surcharge)

Scheune (Jershöft). 1921.

Oil on canvas.

Signed in bottom center. Inscribed with the work number "21i4" on the reverse. 97.5 x 112 cm (38.3 x 44 in).

On the reverse with a depiction in oil painted over by the artist. [CH].

• Expressionist painting at its best: Schmidt-Rottluff combines vibrant colors, sharp edges, bold forms and strong contours to create a compelling composition.

• Starting in 1920, Jershöft on the Baltic Sea became a place of inspiration for the artist and an important creative retreat.

• Paintings by the artist of this outstanding quality and vibrancy are extremely rare on the auction market.

• Rich international history and part of the outstanding Berthold and Else Beitz Collection, Essen, for almost 65 years.

The work is documented in the archive of the Karl and Emy Schmidt-Rottluff Foundation, Berlin.

PROVENANCE: Ferdinand Möller Collection, Berlin (acquired directly from the artist by 1928 at the latest, with the partly handwritten gallery label on the stretcher).

Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit/Michigan (taken into safekeeping on loan from the property of the aforementioned in March 1938, confiscated by the American state as “enemy property” in December 1940).

US-American state property (1950-1957, assumption of ownership of the above-mentioned confiscation on October 30, 1950 by “Vesting Order 15411” of the Office of Alien Property at the Department of Justice).

Maria Möller-Garny, Cologne (through “repurchase” from the US state in 1957, until 1961: Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett).

Berthold and Else Beitz Collection, Essen (acquired from the above through the Galerie Grosshennig, Düsseldorf, in 1961).

Since then in family ownership.

EXHIBITION: Presumably: A collection of modern German art, New York, Anderson Galleries, October 1-20, 1923, cat. no. 230.

50 ausgewählte Werke heutiger Kunst. Ausstellung im Reckendorfhaus, Hedemannstrasse 24, Berlin (Verlagshaus des “Kunstblattes”), November 1928 (no catalog).

Traveling Exhibition Schmidt-Rottluff, Galerie Möller Berlin, Museum Königsberg, Museum Danzig, November 1928 - March 1929 (no catalog).

Frauen in Not (Women in Need), Ausstellung der Internationalen Arbeiterhilfe (IAH), Haus der Juryfreien, Berlin, October 9 - November 1, 1931, cat. no. 322 (Female Farmhand).

Pommersches Landesmuseum, Greifswald (permanent loan, 2015-2024).

Zwei Männer - ein Meer. Pechstein und Schmidt-Rottluff an der Ostsee, Pommersches Landesmuseum, Greifswald, March 29 - June 28, 2015, cat. no. 10 (illustrated).

LITERATURE: Will Grohmann, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Stuttgart 1956, pp. 266 (illustrated in b/w) and p. 292.

- -

Paul Westheim (ed.), 50 ausgewählte Werke heutiger Kunst. Exhibition at the Reckendorfhaus, Hedemannstrasse 24, in: Das Kunstblatt, vol. 13, no. 1, January 1929, p. 365.

Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett, Stuttgart, 36th auction, 1961, lot 462 (illustrated in color on plate 109).

Eberhard Roters, Galerie Ferdinand Möller. Die Geschichte einer Galerie für Moderne Kunst in Deutschland 1917-1956, Berlin 1984, pp. 156 and 227.

Gisela Schirmer, Käthe Kollwitz und die Kunst ihrer Zeit. Positionen zur Geburtenpolitik, Weimar 1998 (illustrated, no. 277: view taken from the exhibition “Frauen in Not”)

ARCHIVE MATERIAL (selection): File card inventory of Galerie Ferdinand Möller (“Scheune, Öl auf Leinwand” by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff), Berlin, Berlinische Galerie, Ferdinand Möller Estate, BG-KA-N/F.Möller-KK3,74 (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/226939/).

Application documents of various artists for the exhibition “Modern German Art” (October 1-20, 1923) at the Anderson Galleries in New York City (USA), Berlinische Galerie Berlin, Ferdinand Möller Estate, BG-GFM-D I,86 (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/281905/).

Business correspondence between Galerie Ferdinand Möller and the Art Collections of the Free City of Danzig, Berlinische Galerie Berlin, Ferdinand Möller Estate, BG-GFM-C, II 1, 587f. (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/211952/).

Business correspondence between the Galerie Ferdinand Möller and Dr. Wilhelm Reinhold Valentiner, Director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit (USA), Berlinische Galerie Berlin, Ferdinand Möller Estate, BG-GFM-C, II 1,115 (et al.) (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/211478/).

Customs invoice and import declaration for 18 oil paintings from the Galerie Ferdinand Möller to the Detroit Institute of Arts, 1938, Berlinische Galerie Berlin, Ferdinand Möller estate, BG-KA-N/F. Möller-66-M66,18-23 (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/248308/).

Department of Justice, Office of Alien Property, Washington D.C. and others: Purchase agreement between the Office of Alien Property of the US Department of Justice Justice Department with Maria Möller-Garny regarding the repurchase of 19 paintings in storage at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Berlinische Galerie Berlin, Ferdinand Möller Estate, BG-KA-N/F.Möller-68-M68,88-89 (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/248263/).

Heise estate, Schönebeck District Museum, installation view of the exhibition “Frauen in Not” (Women in Need) with works by Katharina Heise, Schmidt-Rottluff's paintings "Frau am Meer" and "Scheune".

Oil on canvas.

Signed in bottom center. Inscribed with the work number "21i4" on the reverse. 97.5 x 112 cm (38.3 x 44 in).

On the reverse with a depiction in oil painted over by the artist. [CH].

• Expressionist painting at its best: Schmidt-Rottluff combines vibrant colors, sharp edges, bold forms and strong contours to create a compelling composition.

• Starting in 1920, Jershöft on the Baltic Sea became a place of inspiration for the artist and an important creative retreat.

• Paintings by the artist of this outstanding quality and vibrancy are extremely rare on the auction market.

• Rich international history and part of the outstanding Berthold and Else Beitz Collection, Essen, for almost 65 years.

The work is documented in the archive of the Karl and Emy Schmidt-Rottluff Foundation, Berlin.

PROVENANCE: Ferdinand Möller Collection, Berlin (acquired directly from the artist by 1928 at the latest, with the partly handwritten gallery label on the stretcher).

Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit/Michigan (taken into safekeeping on loan from the property of the aforementioned in March 1938, confiscated by the American state as “enemy property” in December 1940).

US-American state property (1950-1957, assumption of ownership of the above-mentioned confiscation on October 30, 1950 by “Vesting Order 15411” of the Office of Alien Property at the Department of Justice).

Maria Möller-Garny, Cologne (through “repurchase” from the US state in 1957, until 1961: Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett).

Berthold and Else Beitz Collection, Essen (acquired from the above through the Galerie Grosshennig, Düsseldorf, in 1961).

Since then in family ownership.

EXHIBITION: Presumably: A collection of modern German art, New York, Anderson Galleries, October 1-20, 1923, cat. no. 230.

50 ausgewählte Werke heutiger Kunst. Ausstellung im Reckendorfhaus, Hedemannstrasse 24, Berlin (Verlagshaus des “Kunstblattes”), November 1928 (no catalog).

Traveling Exhibition Schmidt-Rottluff, Galerie Möller Berlin, Museum Königsberg, Museum Danzig, November 1928 - March 1929 (no catalog).

Frauen in Not (Women in Need), Ausstellung der Internationalen Arbeiterhilfe (IAH), Haus der Juryfreien, Berlin, October 9 - November 1, 1931, cat. no. 322 (Female Farmhand).

Pommersches Landesmuseum, Greifswald (permanent loan, 2015-2024).

Zwei Männer - ein Meer. Pechstein und Schmidt-Rottluff an der Ostsee, Pommersches Landesmuseum, Greifswald, March 29 - June 28, 2015, cat. no. 10 (illustrated).

LITERATURE: Will Grohmann, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Stuttgart 1956, pp. 266 (illustrated in b/w) and p. 292.

- -

Paul Westheim (ed.), 50 ausgewählte Werke heutiger Kunst. Exhibition at the Reckendorfhaus, Hedemannstrasse 24, in: Das Kunstblatt, vol. 13, no. 1, January 1929, p. 365.

Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett, Stuttgart, 36th auction, 1961, lot 462 (illustrated in color on plate 109).

Eberhard Roters, Galerie Ferdinand Möller. Die Geschichte einer Galerie für Moderne Kunst in Deutschland 1917-1956, Berlin 1984, pp. 156 and 227.

Gisela Schirmer, Käthe Kollwitz und die Kunst ihrer Zeit. Positionen zur Geburtenpolitik, Weimar 1998 (illustrated, no. 277: view taken from the exhibition “Frauen in Not”)

ARCHIVE MATERIAL (selection): File card inventory of Galerie Ferdinand Möller (“Scheune, Öl auf Leinwand” by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff), Berlin, Berlinische Galerie, Ferdinand Möller Estate, BG-KA-N/F.Möller-KK3,74 (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/226939/).

Application documents of various artists for the exhibition “Modern German Art” (October 1-20, 1923) at the Anderson Galleries in New York City (USA), Berlinische Galerie Berlin, Ferdinand Möller Estate, BG-GFM-D I,86 (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/281905/).

Business correspondence between Galerie Ferdinand Möller and the Art Collections of the Free City of Danzig, Berlinische Galerie Berlin, Ferdinand Möller Estate, BG-GFM-C, II 1, 587f. (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/211952/).

Business correspondence between the Galerie Ferdinand Möller and Dr. Wilhelm Reinhold Valentiner, Director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit (USA), Berlinische Galerie Berlin, Ferdinand Möller Estate, BG-GFM-C, II 1,115 (et al.) (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/211478/).

Customs invoice and import declaration for 18 oil paintings from the Galerie Ferdinand Möller to the Detroit Institute of Arts, 1938, Berlinische Galerie Berlin, Ferdinand Möller estate, BG-KA-N/F. Möller-66-M66,18-23 (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/248308/).

Department of Justice, Office of Alien Property, Washington D.C. and others: Purchase agreement between the Office of Alien Property of the US Department of Justice Justice Department with Maria Möller-Garny regarding the repurchase of 19 paintings in storage at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Berlinische Galerie Berlin, Ferdinand Möller Estate, BG-KA-N/F.Möller-68-M68,88-89 (https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/de/collection/item/248263/).

Heise estate, Schönebeck District Museum, installation view of the exhibition “Frauen in Not” (Women in Need) with works by Katharina Heise, Schmidt-Rottluff's paintings "Frau am Meer" and "Scheune".

Artistic and personal renewal after the First World War

The years following the First World War proved to be a particularly fruitful, eventful, and successful time for Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. In 1919, Galerie Ferdinand Möller in Berlin held the first major solo exhibition after the war. In the following period, the number of exhibitions and participation in exhibitions increased sharply. An enthusiastic essay by Ernst Gosebruch, then director of the Essen Art Museum, appears in the art magazine Genius. In 1920, the first monograph on Karl Schmidt-Rottluff was published by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Numerous museums acquired the artist's works, which, after the privations of the war years, now express his enormous artistic creativity and a mature and particularly powerful expressiveness. Schmidt-Rottluff is now one of the most important artists living in Germany.

Artistic work was only possible to a minimal extent during the war. Schmidt-Rottluff was drafted into military service as early as May 1915 and was stationed in Russia and Lithuania until 1918. Initially, he was deployed as a soldier to construct posts, trenches, and barbed wire fortifications. In late 1916, he was transferred to the auditing office of the press department through the intervention of the writer Richard Dehmel. The artist could not devote himself to painting during these years, but he created some woodcuts and sculptures, many of which were unfortunately destroyed during the Second World War.

In the spring after his return, Schmidt-Rottluff marries the photographer Emy Frisch, who also comes from Chemnitz and whom he had already met several years earlier. He establishes new contacts with the sculptors Georg Kolbe, Richard Scheibe, Emy Roeder, and architect Walter Gropius. The artist laboriously tried to detach himself from what he had experienced: “I am very little satisfied with this summer, which, with its oppressive melancholy, found that all too receptive soil. The whole agony of the war years had such an effect that I still could not free myself from it and felt very weak in the process. I have regained some color confidence – but that may be all,” Schmidt-Rottluff wrote to his friend and collector, the art historian Wilhelm Niemeyer, in 1919. (Quoted from: Gerhard Wietek, Schmidt-Rottluff in Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein, Neumünster 1984, p. 62)

The Baltic Sea paradise of Jershöft: a retreat and source of inspiration

In his efforts to come to terms with his wartime experiences, the artist longed for peace, seclusion, and intense encounters with nature. In 1920, he discovered the fishing village of Jershöft [today: Jarosławiec] on the Baltic Sea in what was then called Eastern Pomerania, just a few hours by train from Berlin. Jershöft remained the summer residence of the artist and his family until 1931. They regularly spent the summer months between May and September in the secluded village on the coast, which now proved to be a haven of peace, a place of longing, and a source of great inspiration. Here, the artist came to appreciate the landscape and the simple life far from the big city. He observed the people of Jershöft going about their daily, usually physically demanding work in an unusual rural setting, and finally processed this wealth of impressions and experiences into expressive pictorial ideas entirely without socio-critical undertones. During these creative years, the depictions of workers, fishermen, farmers, and craftsmen, along with the landscapes, are among the most critical pictorial themes of his oeuvre from the 1920s. The experiences Schmidt-Rottluff gained with his expressive woodcuts, which he created towards the end of the war, can now also be found in his painting: Simplified, almost geometrically abstracted forms and generous areas determine the character of the composition, while strong contrasts of light and dark and cold and warm subtly recall the black and white of the woodcuts, but are given a further dimension by the radiance of the colors.

Expressive density in a frenzy of colors

The work offered here, Barn, also stems from this vital creative period. It was painted during Schmidt-Rottluff's second stay in Jershöft in 1921 and attests to his enormous artistic development as well as to the pent-up creative urge that had built up during the war years and which now broke through with great energy in a highly expressive, powerfully colored and dynamic-expressive composition.

The figures, which are not formulated as individuals but rather schematized and greatly simplified, are arranged in a circle, showing a communal togetherness necessary for this life, and are shown frontally except for the female figure on the right, who is kept in cool blue. The painter and the viewer are located in the interior of the barn, in the far corner of the building, separated from the working figures at the entrance by a barrier, a large pile of hay. Although Schmidt-Rottluff places himself amid the action on the side of the workers, he remains an objective observer despite his fascination and interest.

As with the artist's other images of workers, the activity depicted in the picture is not the actual subject of the portrayal, despite the clear motif. Instead, Schmidt-Rottluff impressively explores formal aspects here and elevates them to the central content of the image.

The once distinct dark contours are now broken up, sometimes left out entirely or reduced to shorter contouring lines, allowing the sculptural figures to merge with their surroundings. With their expressive, flat style, the calm, atmospheric, and harmonious compositions of the pre-war years gave way to a “zone painting” that was also based on the colored surface and now contained a wealth of emotions and dynamics. (Will Grohmann, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Stuttgart 1956, p. 106)

Color now takes center stage: it develops a magnificent, radiant life. Schmidt-Rottluff boldly juxtaposes radiant, deep blue with contrasting, bright sun yellow and warming reddish brown with bright, almost gaudy orange-red. The representational is thus dissolved into color with broad, visible brushstrokes in places; forms intertwine and mutate into a colorful, planar painting with angular outlines and an enormous expressive density. [CH]

Provenance

The rural motif of the barn should not be misleading: it is rare to encounter artworks with such a complex, international history.

The painting was likely among the works that the artist loaned to the Anderson Galleries in New York in 1923 for an exhibition of German art. Wilhelm R. Valentiner rejoices in the catalog's preface: “Schmidt-Rottluff appears as the most individual and powerful personality in Germany. In the surety of his artistic advances, he is reminiscent of Van Gogh, without being influenced by him, but he goes much further than Van Gogh. [...] He aspires to the greatest possible simplification of form and expresses his emotions in a condensed way, with powerful lines and vast surfaces of color. He knows how to render the subconscious life of nature and humanity with uncanny power.“ (”Schmidt-Rottluff appears to be the most individual and strongest personality in Germany. In the certainty of his artistic stance, he recalls Van Gogh without being influenced by him, but he goes much further than Van Gogh. [...] He strives for the greatest simplification of form and expresses his emotions in a condensed way, with powerful lines and large areas of color. He understands how to depict the subconscious life of nature and humanity with almost uncanny power.")

Probably shortly thereafter, but before 1928, the art dealer Ferdinand Möller purchased the painting. Möller, a bookseller by trade, began his fabulously successful career in 1912 at the famous Galerie Arnold in Dresden; in 1910, the gallery's owner at the time, Ludwig Gutbier, had presented the epochal exhibition of the “Brücke” artists. In 1913, Möller founded a branch of the Arnold Gallery in Breslau, and then in October 1918, he set up his gallery on Potsdamer Strasse in Berlin. His artists included Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Mueller, Emil Nolde, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and others. Like many other paintings by the “Brücke” group, the work “Barn” remained in the gallery's possession. And Möller sent it to other important exhibitions. In his review of the show “50 ausgewählte Werke heutiger Kunst” (50 selected works of contemporary art) in the magazine “Kunstblatt,” Paul Westheim called the painting “a concept of extraordinary intensity.” It then went on a tour from Berlin to Königsberg and Danzig. Back in Berlin in 1931, the painting was shown in the programmatic exhibition “Women in Need” – as the embodiment of the exploited female farmhand.

However, the tide was soon to turn for modern art. In July 1937, the infamous exhibition “Degenerate Art” opened; the artworks confiscated from museums were finally expropriated by law by Hitler on May 1, 1938. In response, Möller had 19 works, including our painting, shipped to his friend Wilhelm R. Valentiner in Detroit on loan. The German-American art historian had been the Detroit Art Institute director since 1924 and published the first monograph on Karl Schmidt-Rottluff as early as 1920. On October 30, 1950, the Möller collection was confiscated as “enemy property” by the “Vesting Order” of the Department of Justice, Office of Alien Property, and taken over by the US government. After long and arduous negotiations – Ferdinand Möller died in January 1956 – 17 of the paintings sent initially as loans finally arrived in Cologne, where the gallery had been based since 1951, in January 1958. The family donates two paintings, Wassily Kandinsky's “Bild mit weißer Form” from 1913 and Lyonel Feininger's “Grüne Brücke” from 1916, to the Detroit Art Institute and the North Carolina Museum of Arts in Raleigh as compensation.

In 1961, Maria Möller-Garny donated “Scheune” to the Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett. The painting then found its way into the renowned Berthold and Else Beitz Collection in Essen, having been brokered by Wilhelm Grosshennig. [AT]

The years following the First World War proved to be a particularly fruitful, eventful, and successful time for Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. In 1919, Galerie Ferdinand Möller in Berlin held the first major solo exhibition after the war. In the following period, the number of exhibitions and participation in exhibitions increased sharply. An enthusiastic essay by Ernst Gosebruch, then director of the Essen Art Museum, appears in the art magazine Genius. In 1920, the first monograph on Karl Schmidt-Rottluff was published by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Numerous museums acquired the artist's works, which, after the privations of the war years, now express his enormous artistic creativity and a mature and particularly powerful expressiveness. Schmidt-Rottluff is now one of the most important artists living in Germany.

Artistic work was only possible to a minimal extent during the war. Schmidt-Rottluff was drafted into military service as early as May 1915 and was stationed in Russia and Lithuania until 1918. Initially, he was deployed as a soldier to construct posts, trenches, and barbed wire fortifications. In late 1916, he was transferred to the auditing office of the press department through the intervention of the writer Richard Dehmel. The artist could not devote himself to painting during these years, but he created some woodcuts and sculptures, many of which were unfortunately destroyed during the Second World War.

In the spring after his return, Schmidt-Rottluff marries the photographer Emy Frisch, who also comes from Chemnitz and whom he had already met several years earlier. He establishes new contacts with the sculptors Georg Kolbe, Richard Scheibe, Emy Roeder, and architect Walter Gropius. The artist laboriously tried to detach himself from what he had experienced: “I am very little satisfied with this summer, which, with its oppressive melancholy, found that all too receptive soil. The whole agony of the war years had such an effect that I still could not free myself from it and felt very weak in the process. I have regained some color confidence – but that may be all,” Schmidt-Rottluff wrote to his friend and collector, the art historian Wilhelm Niemeyer, in 1919. (Quoted from: Gerhard Wietek, Schmidt-Rottluff in Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein, Neumünster 1984, p. 62)

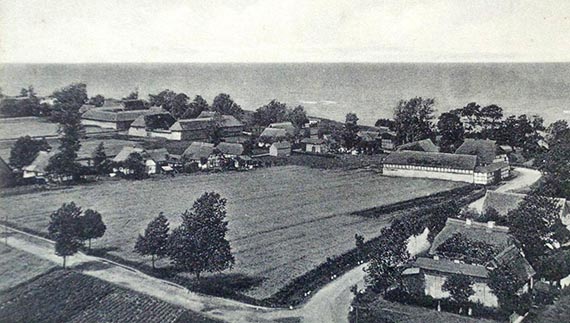

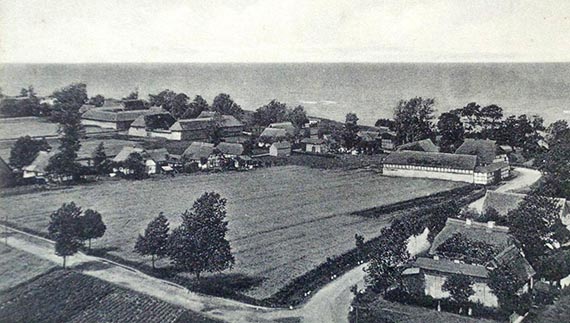

Ostseebad Jershöft, postcard, ca. 1905-1915.

The Baltic Sea paradise of Jershöft: a retreat and source of inspiration

In his efforts to come to terms with his wartime experiences, the artist longed for peace, seclusion, and intense encounters with nature. In 1920, he discovered the fishing village of Jershöft [today: Jarosławiec] on the Baltic Sea in what was then called Eastern Pomerania, just a few hours by train from Berlin. Jershöft remained the summer residence of the artist and his family until 1931. They regularly spent the summer months between May and September in the secluded village on the coast, which now proved to be a haven of peace, a place of longing, and a source of great inspiration. Here, the artist came to appreciate the landscape and the simple life far from the big city. He observed the people of Jershöft going about their daily, usually physically demanding work in an unusual rural setting, and finally processed this wealth of impressions and experiences into expressive pictorial ideas entirely without socio-critical undertones. During these creative years, the depictions of workers, fishermen, farmers, and craftsmen, along with the landscapes, are among the most critical pictorial themes of his oeuvre from the 1920s. The experiences Schmidt-Rottluff gained with his expressive woodcuts, which he created towards the end of the war, can now also be found in his painting: Simplified, almost geometrically abstracted forms and generous areas determine the character of the composition, while strong contrasts of light and dark and cold and warm subtly recall the black and white of the woodcuts, but are given a further dimension by the radiance of the colors.

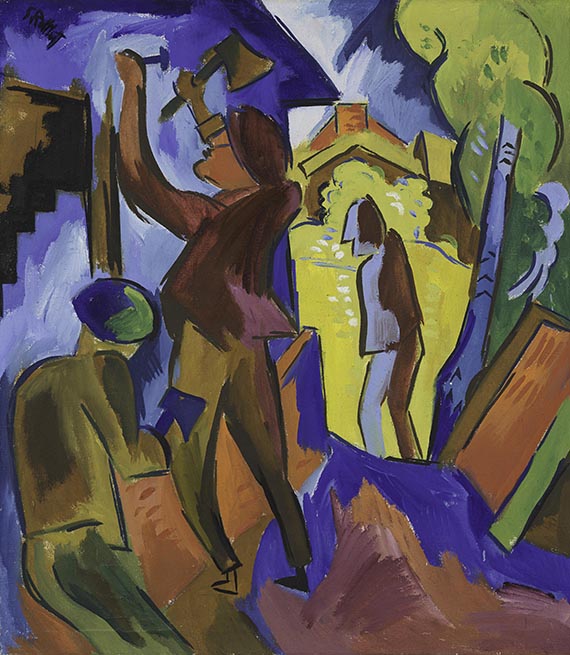

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Handwerker am Haus, 1922, oil on canvas, Brücke-Museum, Berlin. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

Expressive density in a frenzy of colors

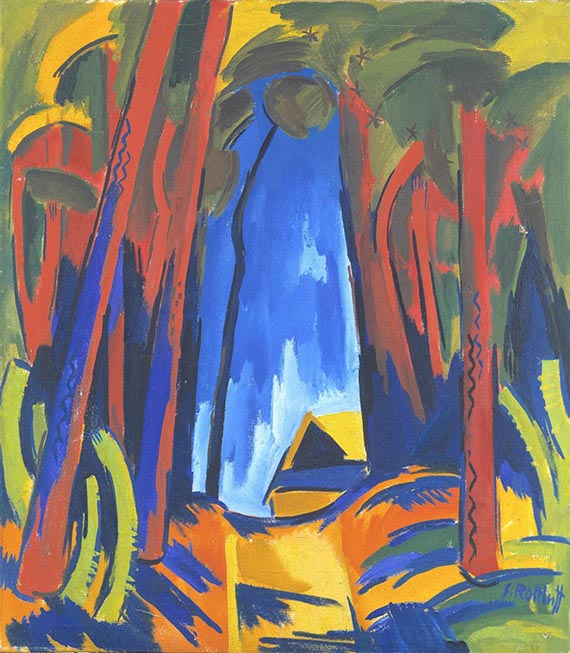

The work offered here, Barn, also stems from this vital creative period. It was painted during Schmidt-Rottluff's second stay in Jershöft in 1921 and attests to his enormous artistic development as well as to the pent-up creative urge that had built up during the war years and which now broke through with great energy in a highly expressive, powerfully colored and dynamic-expressive composition.

The figures, which are not formulated as individuals but rather schematized and greatly simplified, are arranged in a circle, showing a communal togetherness necessary for this life, and are shown frontally except for the female figure on the right, who is kept in cool blue. The painter and the viewer are located in the interior of the barn, in the far corner of the building, separated from the working figures at the entrance by a barrier, a large pile of hay. Although Schmidt-Rottluff places himself amid the action on the side of the workers, he remains an objective observer despite his fascination and interest.

As with the artist's other images of workers, the activity depicted in the picture is not the actual subject of the portrayal, despite the clear motif. Instead, Schmidt-Rottluff impressively explores formal aspects here and elevates them to the central content of the image.

The once distinct dark contours are now broken up, sometimes left out entirely or reduced to shorter contouring lines, allowing the sculptural figures to merge with their surroundings. With their expressive, flat style, the calm, atmospheric, and harmonious compositions of the pre-war years gave way to a “zone painting” that was also based on the colored surface and now contained a wealth of emotions and dynamics. (Will Grohmann, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Stuttgart 1956, p. 106)

Color now takes center stage: it develops a magnificent, radiant life. Schmidt-Rottluff boldly juxtaposes radiant, deep blue with contrasting, bright sun yellow and warming reddish brown with bright, almost gaudy orange-red. The representational is thus dissolved into color with broad, visible brushstrokes in places; forms intertwine and mutate into a colorful, planar painting with angular outlines and an enormous expressive density. [CH]

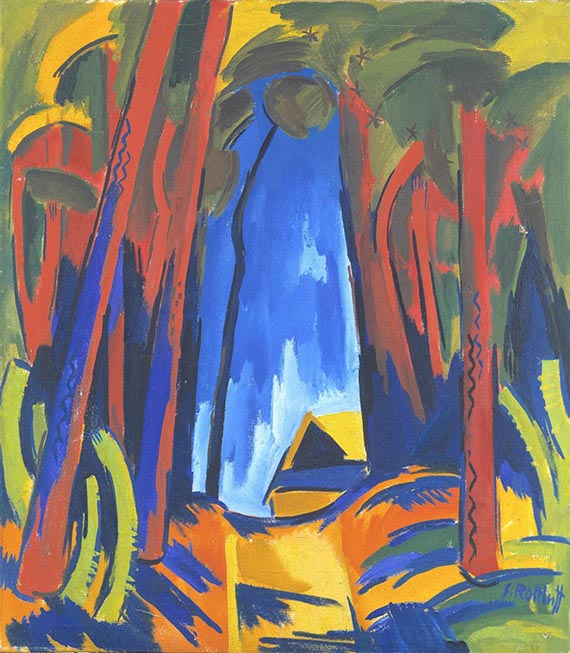

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Waldbild, 1921, oil on canvas, Hamburger Kunsthalle. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

Provenance

The rural motif of the barn should not be misleading: it is rare to encounter artworks with such a complex, international history.

The painting was likely among the works that the artist loaned to the Anderson Galleries in New York in 1923 for an exhibition of German art. Wilhelm R. Valentiner rejoices in the catalog's preface: “Schmidt-Rottluff appears as the most individual and powerful personality in Germany. In the surety of his artistic advances, he is reminiscent of Van Gogh, without being influenced by him, but he goes much further than Van Gogh. [...] He aspires to the greatest possible simplification of form and expresses his emotions in a condensed way, with powerful lines and vast surfaces of color. He knows how to render the subconscious life of nature and humanity with uncanny power.“ (”Schmidt-Rottluff appears to be the most individual and strongest personality in Germany. In the certainty of his artistic stance, he recalls Van Gogh without being influenced by him, but he goes much further than Van Gogh. [...] He strives for the greatest simplification of form and expresses his emotions in a condensed way, with powerful lines and large areas of color. He understands how to depict the subconscious life of nature and humanity with almost uncanny power.")

Probably shortly thereafter, but before 1928, the art dealer Ferdinand Möller purchased the painting. Möller, a bookseller by trade, began his fabulously successful career in 1912 at the famous Galerie Arnold in Dresden; in 1910, the gallery's owner at the time, Ludwig Gutbier, had presented the epochal exhibition of the “Brücke” artists. In 1913, Möller founded a branch of the Arnold Gallery in Breslau, and then in October 1918, he set up his gallery on Potsdamer Strasse in Berlin. His artists included Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Mueller, Emil Nolde, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and others. Like many other paintings by the “Brücke” group, the work “Barn” remained in the gallery's possession. And Möller sent it to other important exhibitions. In his review of the show “50 ausgewählte Werke heutiger Kunst” (50 selected works of contemporary art) in the magazine “Kunstblatt,” Paul Westheim called the painting “a concept of extraordinary intensity.” It then went on a tour from Berlin to Königsberg and Danzig. Back in Berlin in 1931, the painting was shown in the programmatic exhibition “Women in Need” – as the embodiment of the exploited female farmhand.

Our painting shown in the exhibition „Frauen in Not“, an exhibition organised by Internationale Arbeiterhilfe (IAH), Haus der Juryfreien, Berlin, 9.10.-1.11.1931. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

However, the tide was soon to turn for modern art. In July 1937, the infamous exhibition “Degenerate Art” opened; the artworks confiscated from museums were finally expropriated by law by Hitler on May 1, 1938. In response, Möller had 19 works, including our painting, shipped to his friend Wilhelm R. Valentiner in Detroit on loan. The German-American art historian had been the Detroit Art Institute director since 1924 and published the first monograph on Karl Schmidt-Rottluff as early as 1920. On October 30, 1950, the Möller collection was confiscated as “enemy property” by the “Vesting Order” of the Department of Justice, Office of Alien Property, and taken over by the US government. After long and arduous negotiations – Ferdinand Möller died in January 1956 – 17 of the paintings sent initially as loans finally arrived in Cologne, where the gallery had been based since 1951, in January 1958. The family donates two paintings, Wassily Kandinsky's “Bild mit weißer Form” from 1913 and Lyonel Feininger's “Grüne Brücke” from 1916, to the Detroit Art Institute and the North Carolina Museum of Arts in Raleigh as compensation.

In 1961, Maria Möller-Garny donated “Scheune” to the Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett. The painting then found its way into the renowned Berthold and Else Beitz Collection in Essen, having been brokered by Wilhelm Grosshennig. [AT]

38

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

Scheune (Jershöft), 1921.

Oil on canvas

Estimate:

€ 300,000 / $ 339,000 Sold:

€ 558,800 / $ 631,443 (incl. surcharge)

Headquarters

Joseph-Wild-Str. 18

81829 Munich

Phone: +49 89 55 244-0

Fax: +49 89 55 244-177

info@kettererkunst.de

Louisa von Saucken / Undine Schleifer

Holstenwall 5

20355 Hamburg

Phone: +49 40 37 49 61-0

Fax: +49 40 37 49 61-66

infohamburg@kettererkunst.de

Dr. Simone Wiechers / Nane Schlage

Fasanenstr. 70

10719 Berlin

Phone: +49 30 88 67 53-63

Fax: +49 30 88 67 56-43

infoberlin@kettererkunst.de

Cordula Lichtenberg

Gertrudenstraße 24-28

50667 Cologne

Phone: +49 221 510 908-15

infokoeln@kettererkunst.de

Hessen

Rhineland-Palatinate

Miriam Heß

Phone: +49 62 21 58 80-038

Fax: +49 62 21 58 80-595

infoheidelberg@kettererkunst.de

We will inform you in time.

Lot 38

Lot 38