Frame image

213

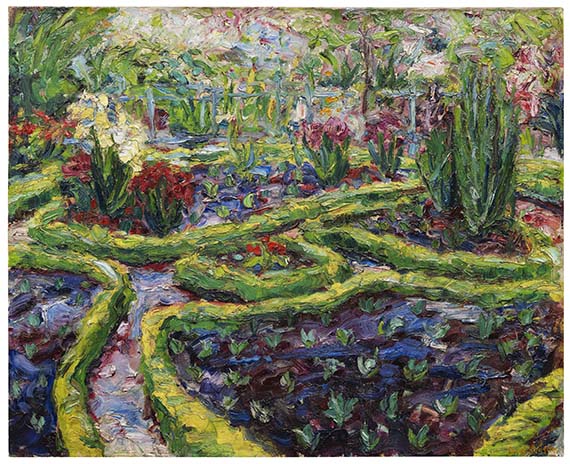

Emil Nolde

Buchsbaumgarten, 1909.

Oil on canvas

Estimate:

€ 1,200,000 / $ 1,356,000 Sold:

€ 2,185,000 / $ 2,469,049 (incl. surcharge)

Buchsbaumgarten. 1909.

Oil on canvas.

Urban 295. Signed in lower left. Once more signed as well as titled on the stretcher. 63 x 78 cm (24.8 x 30.7 in).

Mentioned in the hand-list in 1910 and in 1930.

The painting is mentioned in a letter from Nolde to Gosebruch from December 8, 1910.

• "Buchsbaumgarten" is a witness to the eventful Geman history with all its drama: a work by an artist sympathizing with a contemporary ideology, acquired by a Jewish collector, and a dramatic history that ends in a restitution subject to an amicable agreement.

• The gaudy"Buchsbaumgarten" is one of the works that would pave the path to his future expressionistic endeavours and a document of the artist‘s path to color.

• Nolde‘s works from these days are acknowledged for their museum quality and leading German institutions acquired them right after they were made.

• The avant-gard visionary and director of the Kunstmuseum in Essen, Ernst Gosebruch, avquired the work for his private collection.

Contact Dr. Mario von Lüttichau for more information:

m.luettichau@kettererkunst.de

+49(0) 170 28 69 085

PROVENANCE: Collection Dr. Ernst Gosebruch, Essen (acquired from the artist in 1910/11, until at least January 1, 1921, presumably until March1925).

Presumably Galerie Neue Kunst Fides, Dresden (acquired or on consignment from the above in March 1925).

Collection Dr. Ismar Littmann, Breslau (since 1930 the latest, until September 23, 1934).

From the estate of Dr. Ismar Littmann, Breslau (inherited from Dr. Ismar Littmann on September 23, 1934, until February 26/27, 1935: auction at Max Perl, Berlin).

Dr. Heinrich Arnhold, Dresden (acquired from the above through Max Perl on February 26/27, 1935, until October 10,1935).

Elise (Lisa) Arnhold, Dresden/Zurich/New York (inherited from the above on October 10, 1935, until May 29/30, 1956: auction at Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett).

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Duisburg (acquired from the above through Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett on May 29/30, 1956, until 2021).

Restituted to the heirs after Dr. Ismar Littmann, Wroclaw (2021).

EXHIBITION: Kunstgewerbemuseum Flensburg, 1909.

Essener Kunstverein, April 1910, no. 8.

Kunstverein Jena, June 1910 (painting).

Galerie Commeter, Hamburg, 1910.

Emil Nolde, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon, 1969, no. 5.

"Grupa ‚Die Brücke‘“, Muzeum Narodowe, Wroclaw, 1978, no. 23 (illu. on p. 106).

"German Expressionists“, Hermitage Saint Petersburg, 1981, no. 81.

Brücke. Die Geburt des deutschen Expressionismus, Brücke-Museum, Berlin, October 1, 2005 - January 15, 2006, in cooperation with the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, the Fundacion Caja Madrid and the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, no. 53 with color illu.

LITERATURE: Stefan Koldehoff, Falscher Stolz. Das Lehmbruck-Museum hat jüdische Erben zu lange hingehalten, in: Art 10 (2021), p. 122 with color illu.

Glänzende Aussichten, in: Art 10 (2021), Artplus Auktionen, pp. 149-150 with color illu.

Stefan Koldehoff, Die Bilder sind unter uns. Das Geschäft mit der NS-Raubkunst und der Fall Gurlitt, Cologne 2014, pp. 209-213.

Gesa Jeuthe, Kunstwerte im Wandel. Die Preisentwicklung der deutschen Moderne im nationalen und internationalen Kunstmarkt 1925 bis 1955, Berlin 2011, pp. 315f.

Michael Anton, Rechtshandbuch Kulturgüterschutz und Kunstrestitutionsrecht, vol. 1, Berlin et al 2010, pp. 459-464.

Sylvain Amic (editor), Emil Nolde, accompanying the exhibition of the Réunion at Musées Nationaux, Paris 2008, pp. 112f. with color illu.

Anja Heuß, Die Sammlung Littmann und die Aktion "Entartete Kunst", in: Raub und Restitution. Kulturgut aus jüdischem Besitz von

1933 bis heute, accompanying the exhibition of the Jüdisches Museum Berlin in cooperation with the Jüdisches Museum Frankfurt am Main, Göttingen 2008, pp. 68-74, here p. 74.

Gunnar Schnabel and Monika Tatzkow, Nazi looted art. Handbuch Kunstrestitution weltweit, Berlin 2007, pp. 262-264.

Sabine Rudolph, Restitution von Kunstwerken aus jüdischem Besitz. Dingliche Herausgabeansprüche nach deutschem Recht, Berlin 2007, pp. 5-7.

Hannes Hartung, Kunstraub in Krieg und Verfolgung. Die Restitution der Beute- und Raubkunst im Kollisions- und Völkerrecht, Berlin 2005, pp. 181f.

Mario-Andreas von Lüttichau, "Sonst war Herr Gosebruch sehr nett und gut". Carl Hagemann, Ernst Gosebruch und das Museum Folkwang, in: Eva Mongi-Vollmer (editor), Künstler der Brücke in der Sammlung Hagemann. Kirchner, Heckel, Schmidt-Rottluff, Nolde, Ostfildern-Ruit 2004, pp. 145-153, here p. 150.

Stefan Koldehoff, Wem gehört Noldes Garten?, in: Die Zeit, no. 29, July 10, 2003.

Peter Raue, Summum ius summa iniuria - Geraubtes jüdisches Kultureigentum auf dem Prüfstand des Juristen, in: Andreas Blühm

and Andrea Baresel-Brand (editors), Museen im Zwielicht, Ankaufspolitik 1933-1945, Magdeburg 2007, pp. 289f.

Christoph Brockhaus, Zum Restitutionsgesuch der Erbengemeinschaft Dr. Ismar Littmann für das Ölbild "Buchsbaumgarten" (1909) von Emil Nolde, in: Koordinierungsstelle für Kulturgutverluste (editor), Beiträge öffentlicher Einrichtungen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland zum Umgang mit Kulturgütern aus ehemaligem jüdischen Besitz, Magdeburg 2001, pp. 78-89 with color illu.

Stefan Koldehoff, "Juristisch wie moralisch einwandfrei erworben", in: Art 6 (2000), p. 121, with color illu.

Christoph Brockhaus (editor), Gemälde. Inventory catalog of Wilhelm-Lehmbruck-Museum der Stadt Duisburg, 2nd edition, Duisburg 1999, p. 42.

Lothar-Günther Buchheim, Die Künstlergemeinschaft Brücke, Feldafing 1956, p. 337, illu. 369, p. 401.

Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett, Moderne Kunst. Gemälde, Handzeichnungen, Graphik, Plastik, auction 24 on May 29/30, 1956, lot 944, with illu.

Max Perl, Bücher des 15.-20. Jahrhundert (..), Gemälde, Aquarelle, Handzeichnungen, Graphik, Kunstgewerbe, Plastik, auction on February 26-28, 1935 (catalog no. 188), lot 2556.

Ferdinand Möller to Antonie Kirchhoff, typescript, February 7, 1935 (estate of Ferdinand Möller, Berlinische Galerie, BG-GFM-C,II 1,481-1,511).

Helcia Täubler to Hans Littmann, typescript, January 16, 1935 (Getty Research Institute - Special Collections, Wilhelm Arntz papers, box 17, folder 26-28).

Bernhard Stephan, Inventar der Sammlung Littmann ("Großes Buch"): "Blumengarten".

Oil on canvas.

Urban 295. Signed in lower left. Once more signed as well as titled on the stretcher. 63 x 78 cm (24.8 x 30.7 in).

Mentioned in the hand-list in 1910 and in 1930.

The painting is mentioned in a letter from Nolde to Gosebruch from December 8, 1910.

• "Buchsbaumgarten" is a witness to the eventful Geman history with all its drama: a work by an artist sympathizing with a contemporary ideology, acquired by a Jewish collector, and a dramatic history that ends in a restitution subject to an amicable agreement.

• The gaudy"Buchsbaumgarten" is one of the works that would pave the path to his future expressionistic endeavours and a document of the artist‘s path to color.

• Nolde‘s works from these days are acknowledged for their museum quality and leading German institutions acquired them right after they were made.

• The avant-gard visionary and director of the Kunstmuseum in Essen, Ernst Gosebruch, avquired the work for his private collection.

Contact Dr. Mario von Lüttichau for more information:

m.luettichau@kettererkunst.de

+49(0) 170 28 69 085

PROVENANCE: Collection Dr. Ernst Gosebruch, Essen (acquired from the artist in 1910/11, until at least January 1, 1921, presumably until March1925).

Presumably Galerie Neue Kunst Fides, Dresden (acquired or on consignment from the above in March 1925).

Collection Dr. Ismar Littmann, Breslau (since 1930 the latest, until September 23, 1934).

From the estate of Dr. Ismar Littmann, Breslau (inherited from Dr. Ismar Littmann on September 23, 1934, until February 26/27, 1935: auction at Max Perl, Berlin).

Dr. Heinrich Arnhold, Dresden (acquired from the above through Max Perl on February 26/27, 1935, until October 10,1935).

Elise (Lisa) Arnhold, Dresden/Zurich/New York (inherited from the above on October 10, 1935, until May 29/30, 1956: auction at Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett).

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Duisburg (acquired from the above through Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett on May 29/30, 1956, until 2021).

Restituted to the heirs after Dr. Ismar Littmann, Wroclaw (2021).

EXHIBITION: Kunstgewerbemuseum Flensburg, 1909.

Essener Kunstverein, April 1910, no. 8.

Kunstverein Jena, June 1910 (painting).

Galerie Commeter, Hamburg, 1910.

Emil Nolde, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon, 1969, no. 5.

"Grupa ‚Die Brücke‘“, Muzeum Narodowe, Wroclaw, 1978, no. 23 (illu. on p. 106).

"German Expressionists“, Hermitage Saint Petersburg, 1981, no. 81.

Brücke. Die Geburt des deutschen Expressionismus, Brücke-Museum, Berlin, October 1, 2005 - January 15, 2006, in cooperation with the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, the Fundacion Caja Madrid and the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, no. 53 with color illu.

LITERATURE: Stefan Koldehoff, Falscher Stolz. Das Lehmbruck-Museum hat jüdische Erben zu lange hingehalten, in: Art 10 (2021), p. 122 with color illu.

Glänzende Aussichten, in: Art 10 (2021), Artplus Auktionen, pp. 149-150 with color illu.

Stefan Koldehoff, Die Bilder sind unter uns. Das Geschäft mit der NS-Raubkunst und der Fall Gurlitt, Cologne 2014, pp. 209-213.

Gesa Jeuthe, Kunstwerte im Wandel. Die Preisentwicklung der deutschen Moderne im nationalen und internationalen Kunstmarkt 1925 bis 1955, Berlin 2011, pp. 315f.

Michael Anton, Rechtshandbuch Kulturgüterschutz und Kunstrestitutionsrecht, vol. 1, Berlin et al 2010, pp. 459-464.

Sylvain Amic (editor), Emil Nolde, accompanying the exhibition of the Réunion at Musées Nationaux, Paris 2008, pp. 112f. with color illu.

Anja Heuß, Die Sammlung Littmann und die Aktion "Entartete Kunst", in: Raub und Restitution. Kulturgut aus jüdischem Besitz von

1933 bis heute, accompanying the exhibition of the Jüdisches Museum Berlin in cooperation with the Jüdisches Museum Frankfurt am Main, Göttingen 2008, pp. 68-74, here p. 74.

Gunnar Schnabel and Monika Tatzkow, Nazi looted art. Handbuch Kunstrestitution weltweit, Berlin 2007, pp. 262-264.

Sabine Rudolph, Restitution von Kunstwerken aus jüdischem Besitz. Dingliche Herausgabeansprüche nach deutschem Recht, Berlin 2007, pp. 5-7.

Hannes Hartung, Kunstraub in Krieg und Verfolgung. Die Restitution der Beute- und Raubkunst im Kollisions- und Völkerrecht, Berlin 2005, pp. 181f.

Mario-Andreas von Lüttichau, "Sonst war Herr Gosebruch sehr nett und gut". Carl Hagemann, Ernst Gosebruch und das Museum Folkwang, in: Eva Mongi-Vollmer (editor), Künstler der Brücke in der Sammlung Hagemann. Kirchner, Heckel, Schmidt-Rottluff, Nolde, Ostfildern-Ruit 2004, pp. 145-153, here p. 150.

Stefan Koldehoff, Wem gehört Noldes Garten?, in: Die Zeit, no. 29, July 10, 2003.

Peter Raue, Summum ius summa iniuria - Geraubtes jüdisches Kultureigentum auf dem Prüfstand des Juristen, in: Andreas Blühm

and Andrea Baresel-Brand (editors), Museen im Zwielicht, Ankaufspolitik 1933-1945, Magdeburg 2007, pp. 289f.

Christoph Brockhaus, Zum Restitutionsgesuch der Erbengemeinschaft Dr. Ismar Littmann für das Ölbild "Buchsbaumgarten" (1909) von Emil Nolde, in: Koordinierungsstelle für Kulturgutverluste (editor), Beiträge öffentlicher Einrichtungen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland zum Umgang mit Kulturgütern aus ehemaligem jüdischen Besitz, Magdeburg 2001, pp. 78-89 with color illu.

Stefan Koldehoff, "Juristisch wie moralisch einwandfrei erworben", in: Art 6 (2000), p. 121, with color illu.

Christoph Brockhaus (editor), Gemälde. Inventory catalog of Wilhelm-Lehmbruck-Museum der Stadt Duisburg, 2nd edition, Duisburg 1999, p. 42.

Lothar-Günther Buchheim, Die Künstlergemeinschaft Brücke, Feldafing 1956, p. 337, illu. 369, p. 401.

Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett, Moderne Kunst. Gemälde, Handzeichnungen, Graphik, Plastik, auction 24 on May 29/30, 1956, lot 944, with illu.

Max Perl, Bücher des 15.-20. Jahrhundert (..), Gemälde, Aquarelle, Handzeichnungen, Graphik, Kunstgewerbe, Plastik, auction on February 26-28, 1935 (catalog no. 188), lot 2556.

Ferdinand Möller to Antonie Kirchhoff, typescript, February 7, 1935 (estate of Ferdinand Möller, Berlinische Galerie, BG-GFM-C,II 1,481-1,511).

Helcia Täubler to Hans Littmann, typescript, January 16, 1935 (Getty Research Institute - Special Collections, Wilhelm Arntz papers, box 17, folder 26-28).

Bernhard Stephan, Inventar der Sammlung Littmann ("Großes Buch"): "Blumengarten".

The Boxwood Garden

The flower pictures by Emil Nolde, painted on the island of Alsen from 1906 on, provide the basis for the artist's great color explorations. Both his own garden, laid out by Ada with love and care, and the colorful beds found in his neighborhood, such as the garden of the Burchard family depicted here, contain lush flowerbeds with boxwood borders. Crouched closely together or individually sporting their different colors, a dense sea of flowers spreads out in the painting “Buchsbaumgarten”, surrounded by tall, densely packed shrubs, that fill out the entire format like an ornamental carpet. Narrow gravel paths run between the boxwood-lined, organically shaped beds. With the help of the restless brushstrokes, Nolde depicts a dazzling array of different flowers in bloom. He chose a noticeably narrow image section and completely dispenses with the representation of the sky. The curved paths structure the painting and direct the view into the rear areas of the lavish garden tended to with a lot of empathy for nature. The flower paintings created during this time are particularly fascinating and undoubtedly cast a spell on the observer. The work “Burchard's Garten” from 1907, which was presumably created around the same time, was one of the first works to find its way into the collection of a public museum: The Westphalian State Museum acquired “Burchard's Garten” one year after it was made. The vibrant painting style typical of Nolde‘s works from these days still shows the influence of Impressionism, but with a color intensity inspired by Vincent van Gogh, the step to an independent visual language in which color becomes the predominant means of pictorial expression, is in preparation. In February 1906 the "Brücke" artists convinced the much older painter to join their artist group. Karl Schmidt Rottluff visited him on Alsen for several weeks, both of them had already worked together from time to time. But at the end of the following year, Nolde, who contributed a lot to the group‘s success, left the "Brücke" community. The unmistakable change in the expressiveness of the color, responsible for a change in temperament that became visible in his pictures, is perhaps one of the few treasures that Nolde would gain from his short "Brücke" membership, which, apart from that, was rather depressing for him.

In 1909, the same year the colorful painting “Buchsbaumgarten” was created, Emil Nolde gained increasing artistic recognition; and was asked to join the Berlin Secession. At the same time, however, the living conditions and the artist's environment in the up-and-coming metropolis changed. The events leading to the First World War, which Nolde aptly titled “Jahre der Kämpfe” (Years of Struggle) in his 1934 autobiography, became increasingly stressful for the extremely sensitive artist. Nolde saw the disputes with fellow artists and the associations‘ board members, especially with Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth and Paul Cassirer who dominated the Berlin Secession, more and more critically. The rejection of works from numerous artists by the Secession jury marked a low-point and boosted criticism of the Berlin Secession among wide circles of the Berlin art scene which ultimately led to the immediate establishment of the New Secession. Among others, the jury had rejected Nolde's “Letztes Abendmahl” (Last Supper), also painted in 1909, with which the artist added another focal point to his oeuvre the same year the painting “Buchsbaumgarten” was made: Nolde's examination of of religious themes.

Classification of the painting and its significance against the background of the painter‘s oeuvre by Prof. Dr. Manfred Reuther

The year 1909 was of extraordinary importance for Emil Nolde's artistic development, as it led his creative will and his fundamental desire for expression to a new level of quality that initially even surprised himself. Subliminally, an idiosyncratic pictorial language had developed and internally consolidated, it suddenly saw a breakthrough and found ecstatic expression in first works. Noticeable changes in his personal expression had already shown at an earlier point: for example in the painting "Freigeist" from 1906, as well as over the following years in spontaneous and haunting self-portraits in impetuous and aroused ink drawings, turbulent dance scenes in a sort of "écriture automatique" or the watercolors made in Cospeda near Jena, in which the artist integrated coincidence and the "cooperation of nature". "I often [...] surprised myself with what I had painted and sometimes, as it was the case with the 'Freigeist', outdid myself, I could only grasp the very unwanted things later," notes Nolde in his autobiography.

In addition to numerous landscapes pictures and rural scenes with grazing animals and frolicking village children, the artist, who went through disruptive times, created four paintings with biblical themes in the fishing village of Ruttebüll near the North Sea in the summer of 1909. "With the pictures 'Last Supper' and 'Pentecost', he records in his autobiography, "I performed the transition from the visual external stimulus to the perceived inner value. They became milestones - probably not only in my work", he was convinced. At the same time he ended the early series of pictures that had his Alsen neighbors‘ cottage gardens as motif. One of the last paintings in this series was the "Buchsbaumgarten", an imposing completion created in the garden of the neighboring Burchard family in June, just as he had made comparable paintings in previous years. The painter was familiar with the garden, he knew the motif and was well aware of its compositional possibilities. The foreground is seen from above almost within reach, the rest of the scene is lost in the bright colored light of a more uncertain depth. The early, brightly colored flower and garden pictures, for which Nolde usually preferred a narrow image section and a close view, had soon caught the attention of the young "Brücke" artists.

For years Emil Nolde and his Danish wife Ada Vilstrup had rented a small fisherman's house on the south side of the island close to the edge of a tall beech forest and had also built a little studio shack on the nearby Baltic Sea beach. Inspired by the flowers and gardens, he admitted that he had found color as his true means of expression. "It was in the middle of summer in Alsen. I was irresistibly drawn to the colors of the flowers and almost suddenly found myself painting," he recalls in his autobiography. "The flowers‘ blooming colors and their purity, I loved them." Such statements also attest to his intimate and primal relationship to nature, which was essential for his artistic work. The early flower and garden pictures decisively promoted the development of his personal pictorial language. They are by no means to be classified as a Nolde-avant-Nolde, they are rather an essential, authentic part of a special rank in his entire oeuvre. Under the influence of paintings by Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, whose works he first encountered with great enthusiasm in an exhibition in Weimar in the summer of 1905 after he had returned from a long stay in Sicily. Or through the works by the highly esteemed Edvard Munch, he would attain a free and dynamic painting style that neglected graphic elements. He applied the colors directly onto the canvas with agitated brushstrokes, mostly unbroken; a process that saw thinking as a disruptive influence that should be switched off as much as possible. "The faster I could make a picture," he described his approach, "the better it was. It often took several attempts to arrive at a result [...]." The picture unfolds in the painting process without any preparatory sketches or drafts and grows almost independently from the color like a natural phenomenon, just as it is the case with the "Buchsbaumgarten. "In painting, I always wanted the colors to have as consistent an effect on the canvas as nature has on its own creation," he explains his creative method. "I liked to see the brushstroke in the picture - the script. I wanted to experience the same sensual pleasure in the structure and the colors‘ charm from both a close and a distant perspective."

After returning from the South Sea trip in 1913/1914, Nolde revisited the motif of the garden pictures when visiting the families of his siblings in Northern Schleswig in the summer of 1915. Wherever Nolde settled he arranged flower gardens: whether on the North Sea coast near Ruttebüll, on the dike‘s slope in front of his house Utenwarf, and finally far more generous and richer in Seebüll, where he combined his home and studio to form a total work of art.

Manfred Reuther joined the Ada and Emil Nolde Foundation in Seebüll as a research assistant in 1972; in 1992 he replaced Martin Urban as director of the foundation and remained head until he retired in 2012. He is the globally recognized expert on Emil Nolde's work.

Nolde and the Kunstmuseum in Essen

In 1907 Karl Ernst Osthaus organized the first Nolde exhibition at his Folkwang Museum in Hagen. Nolde's first exhibition in Essen, which Ernst Gosebruch organized in 1910 with the support of the Essener Kunstverein (Essen Art Association) on the premises of the Grillohaus in the city center, was also owed to his recommendation. Ernst Gosebruch was good friends with Osthaus. Not only did he share a liking for contemporary French and German art with the private collector, but as young director of the 1906 founded ‘Essener Kunstsammlung‘, Gosebruch, along with Osthaus, became one of the most progressive museum directors in Germany, and was especially open towards the new art of Expressionism. Gosebruch visited Nolde on Alsen in preparation of the Essen exhibition. "Three of my most beautiful exhibitions were at the Essener Kunstverein and the Folkwang Museum," wrote Nolde in his autobiography "Jahre der Kämpfe". “Ernst Gosebruch valued my art from an early point on. He visited us at the forest house on Alsen . He slept in the small room with the ‘[Christ in] Bethany‘ in it, rising at his feet during his Sunday rest. After he had looked at it for a long time in the morning, he said particularly nice words to us afterwards. We always loved the insightful, artist-friendly person who did not strive for anything shallow in art or for prestige, but who had become the most active museum director. Karl Ernst Osthaus could not have had a more subtle successor for his beautiful Folkwang collection.” (Emil Nolde, Mein Leben, Cologne 1993, p. 223). And Gosebruch was determined to show the “Buchsbaumgarten” along with other flower pictures, landscapes, and - for the first time - paintings with religious themes in Essen.

The exhibition opened on April 3, 1910 and caused quite a stir. The audience in Essen, obviously not yet used to this gaudy painting, at best tolerated the dapper modernity of German Impressionism. “There are new paths that this strange artist is taking, paths entirely unheard of in Essen. Alone, he walks them with a strength and joy that deeply moves art lovers in our city”, wrote Gosebruch to a patron of the museum on April 21 (Emil Nolde. Austellungen in Essen, Essen 1967, p. 10). "How wonderful our friend's bright flower beds and his seascapes ruffled by the fresh wind, on which the light reflections sailed like colorful eggshells hung in the cozy little room that we had set up for the modest event in the side wing toward Surmanngasse," said Gosebruch in his opening speech for Nolde in 1927. He continued: “And between them throned the picture of the Last Supper with the miraculous Christ, which is certainly the deepest, most gracious of all depictions of the Savior in modern art. (Ernst Gosebruch, in: Emil Nolde, ex. cat. Essen 1927, p. 4). Like Osthaus in Hagen, Gosebruch took the 1910 exhibition in Essen as an opportunity to buy a painting for the collection and to use the opportunity to acquire a work by the artist for his own collection. In an undated letter, probably from April / May 1910, Ada Nolde wrote to Gosebruch, who was probably having a hard time making a decision: “From the pictures on offer I would choose the ‘Buxbaumgarten‘ [sic.] for the museum. I think your objections to the yellow woman are wrong, and you would not feel them if you looked at the picture alone. This stagnant heat", Ada Nolde continues,"which the picture emanates, requires a completely different technique than lets say Grober‘s picture, where all the different flowers and colors flicker next to one other. The same is true for the pansy picture. It is simple and strong, does not leave a strong impression in the company of other works, has properties that one must look for and for which one must woo, and is therefore no less valuable.” Gosebruch decided to acquire the “Pansy Picture” for the new art museum and reserved the “Buchsbaumgarten” for his own collection, as Ada Nolde confirmed in another letter to Gosebruch from May 9, 1910: “We are not finical and the museum should have the picture for 1000 M. We would like to include your picture in the Jena exhibition. .... We promised that the works will be in Jena by June 1st the latest. ”And a few days later, on May 27, 1910, Emil Nolde wrote to Gosebruch from Weißernhof, where his wife was staying for medical treatment: “We are pleased to know that the pansy picture will remain in your museum. It is like a sigh of relief when you know that a dear picture has found a good place.“ In 1915 Gosebruch exchanged “Blumengarten. Stiefmütterchen“ (Flower Garden. Pansies), the work‘s correct title, for the painting “Blumengarten H mit Maria” from the same year, which is still part of the Essen collection today. The payment of 900 Marks for the “Buchsbaumgarten” was not made before early January 1911. Ada Nolde had once more made concessions towards Gosebruch regarding its price and urged him to maintain silence about it. Despite initial doubts, Gosebruch eventually acquired this painting “Buchbaumgarten” for his own collection. In a New Year's greeting dated January 1, 1921, Gosebruch informed Nolde that he was considering selling the picture for economic reasons, but would refrain from doing so for the time being. In March 1925, however, according to a reference in the Nolde-Gosebruch correspondence, Gosebruch sent a painting, presumably the “Buchsbaumgarten”, to Rudolf Probst, Galerie Neue Kunst Fides, in Dresden. Could Ismar Littmann, whose contacts to Dresden are known, have bought the work from Probst? In any case, the “Buchsbaumgarten” is recorded in the inventory list of his collection from 1930. This famous “Big Book”, which the art historian Bernhard Stephan created in 1930, contains no less than 347 oil paintings and watercolors - including the painting “Buchsbaumgarten” presented here.

Dr. Ismar Littmann. The Collector

The Wroclaw attorney at law and notary Dr. Ismar Littmann was one of the most active collectors of the art of German Expressionism. Born a merchant's son on July 2, 1878 in Groß Strehlitz, Upper Silesia, he settled in Wroclaw in 1906 as a doctor of law, and took Käthe Fränkel as his wife a little later. Ismar Littmann became a member of the bar at the regional court. He soon established his own law firm, later together with his partner Max Loewe, and was appointed notary in 1921.

The wealthy lawyer Dr. Ismar Littmann was a generous patron and supporter of modern, progressive art. He was particularly committed to contemporary artists from the Academy of Fine Arts in Wroclaw, among them the "Brücke" painter and academy professor Otto Mueller. Today the "Wroclaw artist bohème", which was shaped, promoted and accompanied by the collector and patron Ismar Littmann, is well-known.

From the late 1910s, Dr. Ismar Littmann began to compile his soon-to-be-famous art collection. The Littmann Collection included works by well-known German Impressionists and Expressionists, including Otto Mueller, Käthe Kollwitz, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Alexander Kanoldt and Lovis Corinth. Littmann also had close personal contacts with some of the artists mentioned. Only the global economic crisis in 1929 put an end to his passion for collecting. By then, Littmann had compiled almost 6,000 important works of art, watercolors, drawings and prints as well as paintings.

However, the seizure of power by the National Socialists brought about sudden change. The Jewish lawyer Dr. Ismar Littmann had to face the terrors of persecution from an early point on. His professional group was one of the first that the National Socialists sought to destroy, both economically and socially. As of the spring of 1933, neither Dr. Ismar Littmann nor his children were able to pursue their professions. Deprived of his livelihood and joie de vivre, Ismar Littmann had to face up to the ruins of a once glamorous existence. Deep despair drove him into suicide on September 23, 1934. Ismar Littmann left his widow Käthe and four children behind. With luck, the survivors were later able to flee National Socialist dictatorship.

In order to pay for their escape and to make a living in general, the Littmann family had to sell parts of the important art collection. On February 26 and 27, 1935, around 200 works from the Littmann Collection were offered in a collective auction at the Max Perl auction house in Berlin. Emil Nolde's "Boxwood Garden" was one of them. The auction at Perl was ill-fated, as discussions about so-called "degenerate art" were already in full swing. The Gestapo confiscated 64 paintings, watercolors and drawings, including 18 works of art from the Littmann collection, as examples of "Bolshevik cultural tendencies" before the auction took place. The following year they were handed over to the Nationalgalerie in Berlin. The then director Eberhard Hanfstaengl kept some of the works as "contemporary documents" and, by order of the Gestapo, had the rest of them burned in the furnace of the Kronprinzenpalais on March 23, 1936. (Cf. Annegret Janda, Das Schicksal einer Sammlung, 1986, p. 69). In 1937 the works that Hanfstaengl had ‘rescued’ were also confiscated and defamed in the exhibition "Degenerate Art" in Munich.

Emil Nolde's painting "Buchsbaumgarten" was spared this fate. The Gestapo did not confiscate the painting and it was called up at Max Perl. The work, estimated at 800 Reichsmarks, changed owners in February 1935. It was sold to the Dresden banker Dr. Heinrich Arnhold for the bargain price of just 350 RM, which the widow had to accept in her distress. The Arnholds were also among those persecuted by the Nazi dictatorship, but were able to keep the "Boxwood Garden" safe during these years. Lisa Arnhold herself consigned the painting to an auction at the Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett in 1956, where the Duisburg museum director Gerhard Händler bought it for 3,600 German Marks. (Stefan Koldehoff, Die Bilder sind unter uns. Das Geschäft mit der NS-Raubkunst, Frankfurt a. M. 2009, p. 178ff.)

The outstanding provenance of the painting "Buchsbaumgarten" has caused great international stir in the past, also in context of a long-standing restitution request against the Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg. An amicable agreement was reached in 2021, and the return agreement between the museum and the heirs after Ismar Littmann is a powerful signal for the responsible treatment of artworks from Jewish ownership - at the same time it is yet another exciting moment in the eventful history of an iconic painting.

[Mario-Andreas von Lüttichau]

The flower pictures by Emil Nolde, painted on the island of Alsen from 1906 on, provide the basis for the artist's great color explorations. Both his own garden, laid out by Ada with love and care, and the colorful beds found in his neighborhood, such as the garden of the Burchard family depicted here, contain lush flowerbeds with boxwood borders. Crouched closely together or individually sporting their different colors, a dense sea of flowers spreads out in the painting “Buchsbaumgarten”, surrounded by tall, densely packed shrubs, that fill out the entire format like an ornamental carpet. Narrow gravel paths run between the boxwood-lined, organically shaped beds. With the help of the restless brushstrokes, Nolde depicts a dazzling array of different flowers in bloom. He chose a noticeably narrow image section and completely dispenses with the representation of the sky. The curved paths structure the painting and direct the view into the rear areas of the lavish garden tended to with a lot of empathy for nature. The flower paintings created during this time are particularly fascinating and undoubtedly cast a spell on the observer. The work “Burchard's Garten” from 1907, which was presumably created around the same time, was one of the first works to find its way into the collection of a public museum: The Westphalian State Museum acquired “Burchard's Garten” one year after it was made. The vibrant painting style typical of Nolde‘s works from these days still shows the influence of Impressionism, but with a color intensity inspired by Vincent van Gogh, the step to an independent visual language in which color becomes the predominant means of pictorial expression, is in preparation. In February 1906 the "Brücke" artists convinced the much older painter to join their artist group. Karl Schmidt Rottluff visited him on Alsen for several weeks, both of them had already worked together from time to time. But at the end of the following year, Nolde, who contributed a lot to the group‘s success, left the "Brücke" community. The unmistakable change in the expressiveness of the color, responsible for a change in temperament that became visible in his pictures, is perhaps one of the few treasures that Nolde would gain from his short "Brücke" membership, which, apart from that, was rather depressing for him.

In 1909, the same year the colorful painting “Buchsbaumgarten” was created, Emil Nolde gained increasing artistic recognition; and was asked to join the Berlin Secession. At the same time, however, the living conditions and the artist's environment in the up-and-coming metropolis changed. The events leading to the First World War, which Nolde aptly titled “Jahre der Kämpfe” (Years of Struggle) in his 1934 autobiography, became increasingly stressful for the extremely sensitive artist. Nolde saw the disputes with fellow artists and the associations‘ board members, especially with Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth and Paul Cassirer who dominated the Berlin Secession, more and more critically. The rejection of works from numerous artists by the Secession jury marked a low-point and boosted criticism of the Berlin Secession among wide circles of the Berlin art scene which ultimately led to the immediate establishment of the New Secession. Among others, the jury had rejected Nolde's “Letztes Abendmahl” (Last Supper), also painted in 1909, with which the artist added another focal point to his oeuvre the same year the painting “Buchsbaumgarten” was made: Nolde's examination of of religious themes.

Classification of the painting and its significance against the background of the painter‘s oeuvre by Prof. Dr. Manfred Reuther

The year 1909 was of extraordinary importance for Emil Nolde's artistic development, as it led his creative will and his fundamental desire for expression to a new level of quality that initially even surprised himself. Subliminally, an idiosyncratic pictorial language had developed and internally consolidated, it suddenly saw a breakthrough and found ecstatic expression in first works. Noticeable changes in his personal expression had already shown at an earlier point: for example in the painting "Freigeist" from 1906, as well as over the following years in spontaneous and haunting self-portraits in impetuous and aroused ink drawings, turbulent dance scenes in a sort of "écriture automatique" or the watercolors made in Cospeda near Jena, in which the artist integrated coincidence and the "cooperation of nature". "I often [...] surprised myself with what I had painted and sometimes, as it was the case with the 'Freigeist', outdid myself, I could only grasp the very unwanted things later," notes Nolde in his autobiography.

In addition to numerous landscapes pictures and rural scenes with grazing animals and frolicking village children, the artist, who went through disruptive times, created four paintings with biblical themes in the fishing village of Ruttebüll near the North Sea in the summer of 1909. "With the pictures 'Last Supper' and 'Pentecost', he records in his autobiography, "I performed the transition from the visual external stimulus to the perceived inner value. They became milestones - probably not only in my work", he was convinced. At the same time he ended the early series of pictures that had his Alsen neighbors‘ cottage gardens as motif. One of the last paintings in this series was the "Buchsbaumgarten", an imposing completion created in the garden of the neighboring Burchard family in June, just as he had made comparable paintings in previous years. The painter was familiar with the garden, he knew the motif and was well aware of its compositional possibilities. The foreground is seen from above almost within reach, the rest of the scene is lost in the bright colored light of a more uncertain depth. The early, brightly colored flower and garden pictures, for which Nolde usually preferred a narrow image section and a close view, had soon caught the attention of the young "Brücke" artists.

For years Emil Nolde and his Danish wife Ada Vilstrup had rented a small fisherman's house on the south side of the island close to the edge of a tall beech forest and had also built a little studio shack on the nearby Baltic Sea beach. Inspired by the flowers and gardens, he admitted that he had found color as his true means of expression. "It was in the middle of summer in Alsen. I was irresistibly drawn to the colors of the flowers and almost suddenly found myself painting," he recalls in his autobiography. "The flowers‘ blooming colors and their purity, I loved them." Such statements also attest to his intimate and primal relationship to nature, which was essential for his artistic work. The early flower and garden pictures decisively promoted the development of his personal pictorial language. They are by no means to be classified as a Nolde-avant-Nolde, they are rather an essential, authentic part of a special rank in his entire oeuvre. Under the influence of paintings by Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, whose works he first encountered with great enthusiasm in an exhibition in Weimar in the summer of 1905 after he had returned from a long stay in Sicily. Or through the works by the highly esteemed Edvard Munch, he would attain a free and dynamic painting style that neglected graphic elements. He applied the colors directly onto the canvas with agitated brushstrokes, mostly unbroken; a process that saw thinking as a disruptive influence that should be switched off as much as possible. "The faster I could make a picture," he described his approach, "the better it was. It often took several attempts to arrive at a result [...]." The picture unfolds in the painting process without any preparatory sketches or drafts and grows almost independently from the color like a natural phenomenon, just as it is the case with the "Buchsbaumgarten. "In painting, I always wanted the colors to have as consistent an effect on the canvas as nature has on its own creation," he explains his creative method. "I liked to see the brushstroke in the picture - the script. I wanted to experience the same sensual pleasure in the structure and the colors‘ charm from both a close and a distant perspective."

After returning from the South Sea trip in 1913/1914, Nolde revisited the motif of the garden pictures when visiting the families of his siblings in Northern Schleswig in the summer of 1915. Wherever Nolde settled he arranged flower gardens: whether on the North Sea coast near Ruttebüll, on the dike‘s slope in front of his house Utenwarf, and finally far more generous and richer in Seebüll, where he combined his home and studio to form a total work of art.

Manfred Reuther joined the Ada and Emil Nolde Foundation in Seebüll as a research assistant in 1972; in 1992 he replaced Martin Urban as director of the foundation and remained head until he retired in 2012. He is the globally recognized expert on Emil Nolde's work.

Nolde and the Kunstmuseum in Essen

In 1907 Karl Ernst Osthaus organized the first Nolde exhibition at his Folkwang Museum in Hagen. Nolde's first exhibition in Essen, which Ernst Gosebruch organized in 1910 with the support of the Essener Kunstverein (Essen Art Association) on the premises of the Grillohaus in the city center, was also owed to his recommendation. Ernst Gosebruch was good friends with Osthaus. Not only did he share a liking for contemporary French and German art with the private collector, but as young director of the 1906 founded ‘Essener Kunstsammlung‘, Gosebruch, along with Osthaus, became one of the most progressive museum directors in Germany, and was especially open towards the new art of Expressionism. Gosebruch visited Nolde on Alsen in preparation of the Essen exhibition. "Three of my most beautiful exhibitions were at the Essener Kunstverein and the Folkwang Museum," wrote Nolde in his autobiography "Jahre der Kämpfe". “Ernst Gosebruch valued my art from an early point on. He visited us at the forest house on Alsen . He slept in the small room with the ‘[Christ in] Bethany‘ in it, rising at his feet during his Sunday rest. After he had looked at it for a long time in the morning, he said particularly nice words to us afterwards. We always loved the insightful, artist-friendly person who did not strive for anything shallow in art or for prestige, but who had become the most active museum director. Karl Ernst Osthaus could not have had a more subtle successor for his beautiful Folkwang collection.” (Emil Nolde, Mein Leben, Cologne 1993, p. 223). And Gosebruch was determined to show the “Buchsbaumgarten” along with other flower pictures, landscapes, and - for the first time - paintings with religious themes in Essen.

The exhibition opened on April 3, 1910 and caused quite a stir. The audience in Essen, obviously not yet used to this gaudy painting, at best tolerated the dapper modernity of German Impressionism. “There are new paths that this strange artist is taking, paths entirely unheard of in Essen. Alone, he walks them with a strength and joy that deeply moves art lovers in our city”, wrote Gosebruch to a patron of the museum on April 21 (Emil Nolde. Austellungen in Essen, Essen 1967, p. 10). "How wonderful our friend's bright flower beds and his seascapes ruffled by the fresh wind, on which the light reflections sailed like colorful eggshells hung in the cozy little room that we had set up for the modest event in the side wing toward Surmanngasse," said Gosebruch in his opening speech for Nolde in 1927. He continued: “And between them throned the picture of the Last Supper with the miraculous Christ, which is certainly the deepest, most gracious of all depictions of the Savior in modern art. (Ernst Gosebruch, in: Emil Nolde, ex. cat. Essen 1927, p. 4). Like Osthaus in Hagen, Gosebruch took the 1910 exhibition in Essen as an opportunity to buy a painting for the collection and to use the opportunity to acquire a work by the artist for his own collection. In an undated letter, probably from April / May 1910, Ada Nolde wrote to Gosebruch, who was probably having a hard time making a decision: “From the pictures on offer I would choose the ‘Buxbaumgarten‘ [sic.] for the museum. I think your objections to the yellow woman are wrong, and you would not feel them if you looked at the picture alone. This stagnant heat", Ada Nolde continues,"which the picture emanates, requires a completely different technique than lets say Grober‘s picture, where all the different flowers and colors flicker next to one other. The same is true for the pansy picture. It is simple and strong, does not leave a strong impression in the company of other works, has properties that one must look for and for which one must woo, and is therefore no less valuable.” Gosebruch decided to acquire the “Pansy Picture” for the new art museum and reserved the “Buchsbaumgarten” for his own collection, as Ada Nolde confirmed in another letter to Gosebruch from May 9, 1910: “We are not finical and the museum should have the picture for 1000 M. We would like to include your picture in the Jena exhibition. .... We promised that the works will be in Jena by June 1st the latest. ”And a few days later, on May 27, 1910, Emil Nolde wrote to Gosebruch from Weißernhof, where his wife was staying for medical treatment: “We are pleased to know that the pansy picture will remain in your museum. It is like a sigh of relief when you know that a dear picture has found a good place.“ In 1915 Gosebruch exchanged “Blumengarten. Stiefmütterchen“ (Flower Garden. Pansies), the work‘s correct title, for the painting “Blumengarten H mit Maria” from the same year, which is still part of the Essen collection today. The payment of 900 Marks for the “Buchsbaumgarten” was not made before early January 1911. Ada Nolde had once more made concessions towards Gosebruch regarding its price and urged him to maintain silence about it. Despite initial doubts, Gosebruch eventually acquired this painting “Buchbaumgarten” for his own collection. In a New Year's greeting dated January 1, 1921, Gosebruch informed Nolde that he was considering selling the picture for economic reasons, but would refrain from doing so for the time being. In March 1925, however, according to a reference in the Nolde-Gosebruch correspondence, Gosebruch sent a painting, presumably the “Buchsbaumgarten”, to Rudolf Probst, Galerie Neue Kunst Fides, in Dresden. Could Ismar Littmann, whose contacts to Dresden are known, have bought the work from Probst? In any case, the “Buchsbaumgarten” is recorded in the inventory list of his collection from 1930. This famous “Big Book”, which the art historian Bernhard Stephan created in 1930, contains no less than 347 oil paintings and watercolors - including the painting “Buchsbaumgarten” presented here.

Dr. Ismar Littmann. The Collector

The Wroclaw attorney at law and notary Dr. Ismar Littmann was one of the most active collectors of the art of German Expressionism. Born a merchant's son on July 2, 1878 in Groß Strehlitz, Upper Silesia, he settled in Wroclaw in 1906 as a doctor of law, and took Käthe Fränkel as his wife a little later. Ismar Littmann became a member of the bar at the regional court. He soon established his own law firm, later together with his partner Max Loewe, and was appointed notary in 1921.

The wealthy lawyer Dr. Ismar Littmann was a generous patron and supporter of modern, progressive art. He was particularly committed to contemporary artists from the Academy of Fine Arts in Wroclaw, among them the "Brücke" painter and academy professor Otto Mueller. Today the "Wroclaw artist bohème", which was shaped, promoted and accompanied by the collector and patron Ismar Littmann, is well-known.

From the late 1910s, Dr. Ismar Littmann began to compile his soon-to-be-famous art collection. The Littmann Collection included works by well-known German Impressionists and Expressionists, including Otto Mueller, Käthe Kollwitz, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Alexander Kanoldt and Lovis Corinth. Littmann also had close personal contacts with some of the artists mentioned. Only the global economic crisis in 1929 put an end to his passion for collecting. By then, Littmann had compiled almost 6,000 important works of art, watercolors, drawings and prints as well as paintings.

However, the seizure of power by the National Socialists brought about sudden change. The Jewish lawyer Dr. Ismar Littmann had to face the terrors of persecution from an early point on. His professional group was one of the first that the National Socialists sought to destroy, both economically and socially. As of the spring of 1933, neither Dr. Ismar Littmann nor his children were able to pursue their professions. Deprived of his livelihood and joie de vivre, Ismar Littmann had to face up to the ruins of a once glamorous existence. Deep despair drove him into suicide on September 23, 1934. Ismar Littmann left his widow Käthe and four children behind. With luck, the survivors were later able to flee National Socialist dictatorship.

In order to pay for their escape and to make a living in general, the Littmann family had to sell parts of the important art collection. On February 26 and 27, 1935, around 200 works from the Littmann Collection were offered in a collective auction at the Max Perl auction house in Berlin. Emil Nolde's "Boxwood Garden" was one of them. The auction at Perl was ill-fated, as discussions about so-called "degenerate art" were already in full swing. The Gestapo confiscated 64 paintings, watercolors and drawings, including 18 works of art from the Littmann collection, as examples of "Bolshevik cultural tendencies" before the auction took place. The following year they were handed over to the Nationalgalerie in Berlin. The then director Eberhard Hanfstaengl kept some of the works as "contemporary documents" and, by order of the Gestapo, had the rest of them burned in the furnace of the Kronprinzenpalais on March 23, 1936. (Cf. Annegret Janda, Das Schicksal einer Sammlung, 1986, p. 69). In 1937 the works that Hanfstaengl had ‘rescued’ were also confiscated and defamed in the exhibition "Degenerate Art" in Munich.

Emil Nolde's painting "Buchsbaumgarten" was spared this fate. The Gestapo did not confiscate the painting and it was called up at Max Perl. The work, estimated at 800 Reichsmarks, changed owners in February 1935. It was sold to the Dresden banker Dr. Heinrich Arnhold for the bargain price of just 350 RM, which the widow had to accept in her distress. The Arnholds were also among those persecuted by the Nazi dictatorship, but were able to keep the "Boxwood Garden" safe during these years. Lisa Arnhold herself consigned the painting to an auction at the Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett in 1956, where the Duisburg museum director Gerhard Händler bought it for 3,600 German Marks. (Stefan Koldehoff, Die Bilder sind unter uns. Das Geschäft mit der NS-Raubkunst, Frankfurt a. M. 2009, p. 178ff.)

The outstanding provenance of the painting "Buchsbaumgarten" has caused great international stir in the past, also in context of a long-standing restitution request against the Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg. An amicable agreement was reached in 2021, and the return agreement between the museum and the heirs after Ismar Littmann is a powerful signal for the responsible treatment of artworks from Jewish ownership - at the same time it is yet another exciting moment in the eventful history of an iconic painting.

[Mario-Andreas von Lüttichau]

213

Emil Nolde

Buchsbaumgarten, 1909.

Oil on canvas

Estimate:

€ 1,200,000 / $ 1,356,000 Sold:

€ 2,185,000 / $ 2,469,049 (incl. surcharge)

Headquarters

Joseph-Wild-Str. 18

81829 Munich

Phone: +49 89 55 244-0

Fax: +49 89 55 244-177

info@kettererkunst.de

Louisa von Saucken / Undine Schleifer

Holstenwall 5

20355 Hamburg

Phone: +49 40 37 49 61-0

Fax: +49 40 37 49 61-66

infohamburg@kettererkunst.de

Dr. Simone Wiechers / Nane Schlage

Fasanenstr. 70

10719 Berlin

Phone: +49 30 88 67 53-63

Fax: +49 30 88 67 56-43

infoberlin@kettererkunst.de

Cordula Lichtenberg

Gertrudenstraße 24-28

50667 Cologne

Phone: +49 221 510 908-15

infokoeln@kettererkunst.de

Hessen

Rhineland-Palatinate

Miriam Heß

Phone: +49 62 21 58 80-038

Fax: +49 62 21 58 80-595

infoheidelberg@kettererkunst.de

We will inform you in time.

Lot 213

Lot 213