193

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

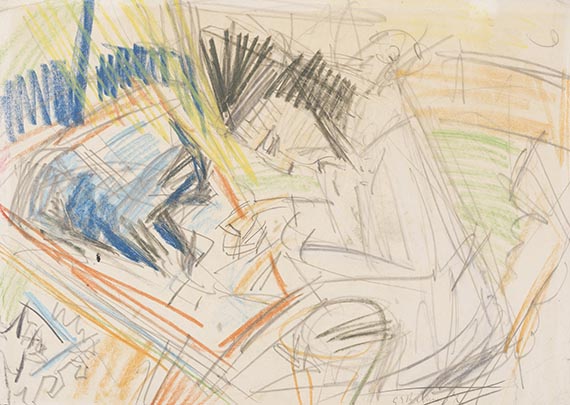

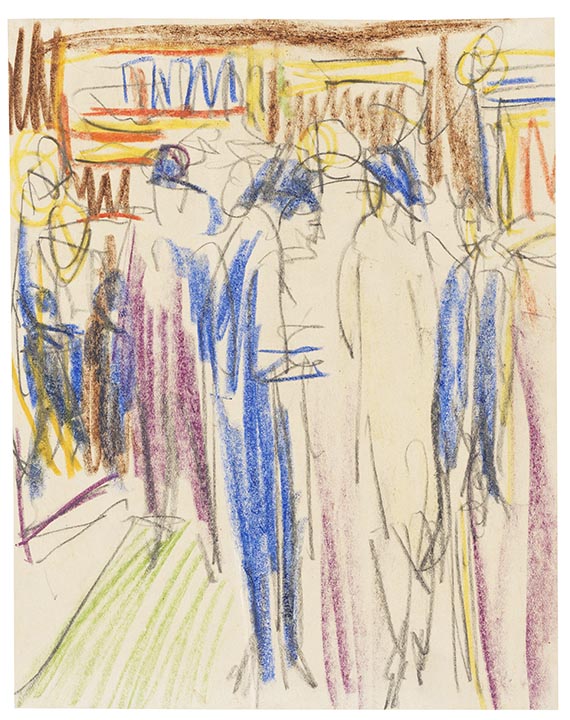

Erna Schilling mit Kater Boby (Frau mit Katze), Um 1919.

Colored chalk drawing

Post auction sale: € 14,000 / $ 16,520

Erna Schilling mit Kater Boby (Frau mit Katze). Um 1919.

Colored chalk drawing.

Signed in the lower right corner and on the reverse. On creme wove paper. 41.3 x 56.2 cm (16.2 x 22.1 in), the full sheet.

With a drawing of female nudes ("Badende", probably his models Erna and Gerda), pencil, around 1915, on the reverse. [CH].

• Detailed, colorful drawing with particularly dense, dynamic lines.

• Sheet painted on both sides, with a pencil drawing of two female nudes (circa 1915) on the reverse.

• Kirchner was drawn to Switzerland, and Davos eventually became his new home.

• Kirchner's very private world: his cat Boby was his faithful companion until he died in 1930.

• Immediate, spontaneous, yet accurate depiction of the artist's observations.

This work is documented in the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive, Wichtrach/Bern.

We are grateful to Prof. Dr. Dr. Gerd Presler for his expert advice and kind support in cataloging this work.

PROVENANCE: Probably Galerie Valentien, Stuttgart (with the gallery label on the back of the frame).

Private collection, Baden-Württemberg.

Private collection, Germany (acquired from the above).

Private collection, South Germany (probably acquired from the above in the 1950s).

Private collection, South Germany (inherited from the above in 2006).

Before settling permanently in Switzerland, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner traveled to Davos numerous times to seek treatment for his health from Dr. Frédéric Bauer, then chief physician at the Davos Park Sanatorium. He also spent the summer of 1918 in his beloved Swiss mountain retreat. Finally, he rented the house “In den Lärchen” in Frauenkirch the following winter, where he created this colorful chalk drawing of his partner Erna Schilling doing needlework and their cat “Boby” in 1919.

During those summer days, Kirchner wrote: “Boby, the little tomcat, is here now. Clean and lively, quite interesting company. I have a picture of a cat on the carpet and a nude in mind; it must be a fine piece of work,” and later: “I have to draw until my fingers bleed, just draw. Then, after some time, choose the best ones. The technique [is] too beautiful. Boby and mother cat done.” (E. L. Kirchner, July 30, 1919, and August 4, 1919, quoted from: L. Grisebach, Kirchners Davoser Tagebuch, Wichtrach 1997, p. 40f.)

“This creative frenzy finds its initial outlet in his sketchbooks (cf. Presler Skb 64-24, -25, -29), and also in this drawing, which is characterized by Kirchner's creative energy and powerful strokes.” (Prof. Dr. Dr. Gerd Presler)

Colored chalk drawing.

Signed in the lower right corner and on the reverse. On creme wove paper. 41.3 x 56.2 cm (16.2 x 22.1 in), the full sheet.

With a drawing of female nudes ("Badende", probably his models Erna and Gerda), pencil, around 1915, on the reverse. [CH].

• Detailed, colorful drawing with particularly dense, dynamic lines.

• Sheet painted on both sides, with a pencil drawing of two female nudes (circa 1915) on the reverse.

• Kirchner was drawn to Switzerland, and Davos eventually became his new home.

• Kirchner's very private world: his cat Boby was his faithful companion until he died in 1930.

• Immediate, spontaneous, yet accurate depiction of the artist's observations.

This work is documented in the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive, Wichtrach/Bern.

We are grateful to Prof. Dr. Dr. Gerd Presler for his expert advice and kind support in cataloging this work.

PROVENANCE: Probably Galerie Valentien, Stuttgart (with the gallery label on the back of the frame).

Private collection, Baden-Württemberg.

Private collection, Germany (acquired from the above).

Private collection, South Germany (probably acquired from the above in the 1950s).

Private collection, South Germany (inherited from the above in 2006).

Before settling permanently in Switzerland, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner traveled to Davos numerous times to seek treatment for his health from Dr. Frédéric Bauer, then chief physician at the Davos Park Sanatorium. He also spent the summer of 1918 in his beloved Swiss mountain retreat. Finally, he rented the house “In den Lärchen” in Frauenkirch the following winter, where he created this colorful chalk drawing of his partner Erna Schilling doing needlework and their cat “Boby” in 1919.

During those summer days, Kirchner wrote: “Boby, the little tomcat, is here now. Clean and lively, quite interesting company. I have a picture of a cat on the carpet and a nude in mind; it must be a fine piece of work,” and later: “I have to draw until my fingers bleed, just draw. Then, after some time, choose the best ones. The technique [is] too beautiful. Boby and mother cat done.” (E. L. Kirchner, July 30, 1919, and August 4, 1919, quoted from: L. Grisebach, Kirchners Davoser Tagebuch, Wichtrach 1997, p. 40f.)

“This creative frenzy finds its initial outlet in his sketchbooks (cf. Presler Skb 64-24, -25, -29), and also in this drawing, which is characterized by Kirchner's creative energy and powerful strokes.” (Prof. Dr. Dr. Gerd Presler)

193

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Erna Schilling mit Kater Boby (Frau mit Katze), Um 1919.

Colored chalk drawing

Post auction sale: € 14,000 / $ 16,520

Buyer's premium and taxation for Ernst Ludwig Kirchner "Erna Schilling mit Kater Boby (Frau mit Katze)"

This lot can be purchased subject to differential or regular taxation.

Differential taxation:

Hammer price up to 800,000 €: herefrom 32 % premium.

The share of the hammer price exceeding 800,000 € is subject to a premium of 27 % and is added to the premium of the share of the hammer price up to 800,000 €.

The share of the hammer price exceeding 4,000,000 € is subject to a premium of 22 % and is added to the premium of the share of the hammer price up to 4,000,000 €.

The buyer's premium contains VAT, however, it is not shown.

Regular taxation:

Hammer price up to 800,000 €: herefrom 27 % premium.

The share of the hammer price exceeding 800,000 € is subject to a premium of 21% and is added to the premium of the share of the hammer price up to 800,000 €.

The share of the hammer price exceeding 4,000,000 € is subject to a premium of 15% and is added to the premium of the share of the hammer price up to 4,000,000 €.

The statutory VAT of currently 7 % is levied to the sum of hammer price and premium.

We kindly ask you to notify us before invoicing if you wish to be subject to regular taxation.

Differential taxation:

Hammer price up to 800,000 €: herefrom 32 % premium.

The share of the hammer price exceeding 800,000 € is subject to a premium of 27 % and is added to the premium of the share of the hammer price up to 800,000 €.

The share of the hammer price exceeding 4,000,000 € is subject to a premium of 22 % and is added to the premium of the share of the hammer price up to 4,000,000 €.

The buyer's premium contains VAT, however, it is not shown.

Regular taxation:

Hammer price up to 800,000 €: herefrom 27 % premium.

The share of the hammer price exceeding 800,000 € is subject to a premium of 21% and is added to the premium of the share of the hammer price up to 800,000 €.

The share of the hammer price exceeding 4,000,000 € is subject to a premium of 15% and is added to the premium of the share of the hammer price up to 4,000,000 €.

The statutory VAT of currently 7 % is levied to the sum of hammer price and premium.

We kindly ask you to notify us before invoicing if you wish to be subject to regular taxation.

Headquarters

Joseph-Wild-Str. 18

81829 Munich

Phone: +49 89 55 244-0

Fax: +49 89 55 244-177

info@kettererkunst.de

Louisa von Saucken / Undine Schleifer

Holstenwall 5

20355 Hamburg

Phone: +49 40 37 49 61-0

Fax: +49 40 37 49 61-66

infohamburg@kettererkunst.de

Dr. Simone Wiechers / Nane Schlage

Fasanenstr. 70

10719 Berlin

Phone: +49 30 88 67 53-63

Fax: +49 30 88 67 56-43

infoberlin@kettererkunst.de

Cordula Lichtenberg

Gertrudenstraße 24-28

50667 Cologne

Phone: +49 221 510 908-15

infokoeln@kettererkunst.de

Hessen

Rhineland-Palatinate

Miriam Heß

Phone: +49 62 21 58 80-038

Fax: +49 62 21 58 80-595

infoheidelberg@kettererkunst.de

We will inform you in time.

Lot 193

Lot 193